Pet cats can bring love into your world, but if not cared for properly they can also bring unwanted visitors such as diseases like toxoplasmosis, writes Tida Nou.

Cats bring love, comfort, companionship, laughter and amusement to many people. And the love of cats is not confined to pet cat owners – just think of the many people who love a good internet meme, cat filter or YouTube clip. And then there’s the wildly popular Grumpy Cat!

The rise of cat-cuddle cafes and activities such as ‘yoga with cats’, ‘board games with cats’, ‘lunch break with cats’ and even ‘origami with cats’ is testament to the special place cats hold in many peoples’ hearts, in Australia and elsewhere.

But unfortunately, the animals we love sometimes come with unwanted, and invisible extras. Some of our beloved pet cats carry cat-dependent diseases that can be passed onto humans, including toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, and cat scratch disease.

We don’t really hear much about these cat-dependent diseases, caused by pathogens that need cats for part of their life cycle (without cats, the pathogens can’t persist).

However, recent research by the Threatened Species Recovery Hub indicates these diseases inflict a substantial toll on human health in Australia.

First, let’s take a closer look at toxoplasmosis, or ‘toxo’, as it is commonly called.

The parasite that causes toxoplasmosis, Toxoplasma gondii, is common around the world. In Australia, it was introduced when cats were brought here by European settlers, and is now present in a wide range of native wildlife, both terrestrial and marine.

Toxoplasma gondii has been documented in small mammals such as brushtail and ringtail possums, bandicoots, quokkas, antechinus, phascogales and dunnarts. It has also been recorded in a range of bird species, including Torres Strait pigeons, wonga pigeons, regent and superb parrots, crimson rosellas and satin and regent bowerbirds.

Some of these native species occur in urban areas of Australia. Pet cats allowed to roam can become infected if they eat infected native animals. Pet cats may roam and hunt in quite a large area – the mean home range of a pet cat allowed to roam is two hectares (about the size of two sports fields).

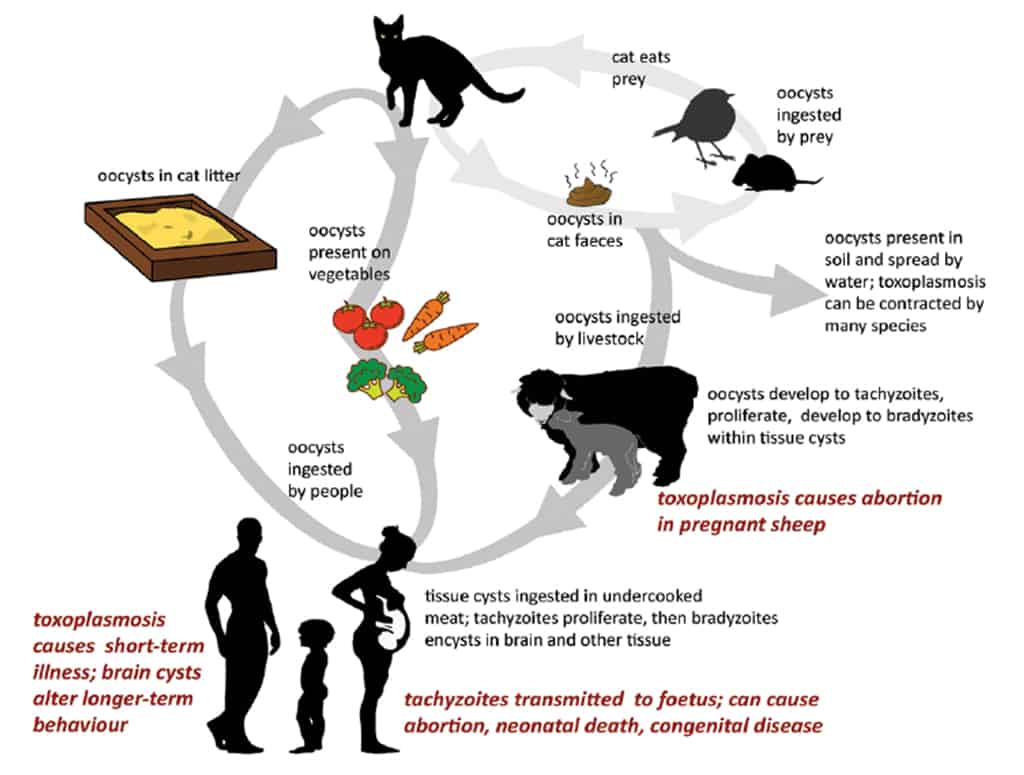

Once a cat is infected, the parasite moves into its small intestine, where it sexually reproduces, producing oocysts (an egg-type life stage).

An infected cat sheds millions of oocysts in their faeces for around 2-3 weeks. And cats generally do not show any symptoms, so owners may not be aware their cat is infected. The cat will then develop an immune response, and stop shedding oocysts (Figure 1).

Cats to people

People can become infected by inadvertently ingesting the oocysts, or the cysts that have formed in infected animals. This can occur in a number of ways including:

- Eating raw or undercooked infected meat.

- Accidentally ingesting contaminated soil (through gardening activity, or on fruit and vegetables).

- Playing in an infected sandpit.

- Handling kitty litter from an infected cat.

Toxoplasmosis has a range of impacts once it infects a person, and while most are unaware of having the disease and show no symptoms at all, others may experience flu-like symptoms, and a smaller proportion become very sick.

Should you be worried?

So, how common is it, how worried should we be, and what can we do about it?

It is estimated that worldwide, around 30% of people are infected. In Australia, estimates for infection rates range between 23 to 66% of the population. A CSIRO study found that 50-62% of Tasmanians have been infected with the parasite. It is not a notifiable disease, so the data available is quite patchy.

Toxoplasmosis is of greatest concern for pregnant women, and immune-compromised people. If a woman is infected during pregnancy, it can potentially cause miscarriage, or abnormalities in newborn babies (such as blindness and brain damage). For immuno-compromised people, there is a risk of severe illness, including brain swelling and other neurological issues.

Alarmingly, even if the initial infection doesn’t cause any illness, the parasite stays with infected people for life, encased in a cyst, often in the brain. Such latent infections can affect mental health and behaviour, including delaying reaction times. You can read more about the impacts and implications of cat-dependent diseases in our fact sheet.

Other cat-dependent diseases are cat-scratch disease (caused by the bacterium Bartonella henselae) and toxocariasis, an infection caused by cat roundworms (Toxocara cati).

Cats are Australia’s second most popular pet, and their numbers are likely to increase as the human population grows. Pet cats provide many benefits to their owners, and we can continue to enjoy their company while also reducing the potential impacts of cat-dependent diseases.

There are two key actions pet cat owners can take to minimise the risk their beloved pet could spread disease to other people and native wildlife:

- Keeping pet cats indoors, or in a securely contained outdoor area will prevent them encountering infected native wildlife, and subsequently infecting children’s sandpits, neighbours’ vegetable gardens, school and local community gardens.

- Cat owners should dispose of cat litter in general waste, rather than using it as garden mulch, or flushing it down the toilet. While this means it will go to landfill, this is the safest option in terms of reducing risks of disease transmission to people.

These actions will reduce the likelihood of pet cats contracting (and therefore passing on) a disease-causing pathogen to people.

Fact sheet

Get the facts on the hidden costs of cats in Australia by downloading the Threatened Species Recovery Hub fact sheet Cat-dependent diseases and human health.

References

Legge, S., Taggart, P., Dickman, C., Read, J., & Woinarski, J. C. Z. (2020). Cat-dependent diseases cost Australia AU$6 billion per year through impacts on human health and livestock production. Wildlife Research 47, 731–746.

Woinarski, J.C.Z., Legge, S.M., Dickman, C.R. 2019. Cats in Australia: Companion and Killer. CSIRO Publishing, p. 156.