The old adage prevention is the best medicine applies to many things, including invasive species – plants, animals or even diseases that are not native to Australia, but once they arrive can quickly become a problem.

Stopping new, environmentally harmful invasive species from arriving and establishing in Australia is one of the most cost-effective actions we can take to protect our native species from invading weeds, feral animals and diseases.

With the coronavirus now a global pandemic most people around the world now understand the need to act hard and fast when a dangerous new virus emerges. The same case can be made for the arrival of invasive species.

In Australia we have seen time and time again what happens when an environmentally destructive weed or pest animal gets out of control. Think of the rapid spread of rabbits and cane toads.

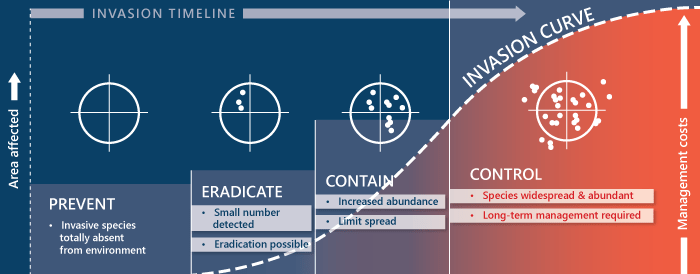

Invasion curve

As their populations grow and spread out so too does the cost of managing their impacts. The invasion curve, which describes the ecological process of arrival and spread of an invasive species, neatly describes the process.

As the invasion curve shows, if we fail to act quickly a pest will become established and we will have lost the chance to eradicate it. The pest species then becomes an ongoing issue for state and federal governments, which need to manage its impacts. It also becomes an ongoing threat to our natural values, our native species, and an ongoing drag on budgets.

A 2016 review of introduced pest animals found they cost the Australian economy between $720 million and $1 billion a year (NRC 2016 State-wide review of pest animal management). A 2019 review found that managing weeds and associated production losses cost $4.8 billion a year. These costs don’t count the environmental impacts.

Know your enemy

Although biological control agents can provide relief for some established pests, as we saw with prickly pear and rabbits, they are not always reliable.

An effective biosecurity system relies on knowing your enemy. While we know much about which diseases and pest species threaten Australia’s farming and health sectors, we know far, far less about which species are a risk for our natural environment.

However, recent research conducted by Monash University in collaboration with the Invasive Species Council and funded by the Ian Potter Foundation is starting to close that gap.

The Risks and Pathways Project set out to identify insect species from other countries that, if they ever reach Australia, have the potential to cause great harm to our natural world.

A stocktake of invasive insects causing environmental harm elsewhere in the world was compiled, their pathways mapped and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) framework for the Environmental Impact Classification of Alien Taxa applied to assess the severity of each species’ ecological impacts.

A national priority list of 247 potential harmful insect invaders was identified. The project also identified the most likely pathways these species would take to infiltrate Australia’s biosecurity system – contamination of imported plants, nursery material or the timber trade.

Further work by the agricultural research body ABARES has looked at all exotic environmental pests and diseases that could establish in Australia. This work will be used by federal and state governments to create a priority list to inform environmental biosecurity activities. The results of the Risks and Pathways Project will also be considered.

Research is vital

Research is vital to a strong environmental biosecurity system. Understanding which invasive species not yet in Australia pose the greatest threats to our natural world and how they could breach our biosecurity borders will allow us to create effective early detection systems, emergency response plans for when incursions do occur and to stop potential environmental invaders at their source.

Had we detected red fire ants shortly after they established in the Brisbane suburb of Wacool we could probably could have eradicated them before the population had an opportunity to spread further afield.

Early detection could have saved the country much of the roughly $800 million that will be spent eradicating this invasive ant by 2027. Instead, it is believed the fire ants were present for more than a decade before they were detected by authorities.

At the peak of the Australian infestation red fire ants covered more than 400,000 ha, that’s an area almost twice the size of the ACT.

Research is needed

The Invasive Species Council has been calling for a greater investment in research to support environmental biosecurity at all stages of the invasion curve: prevention, eradication, containment and control.

We also want greater investment into all invasive species – vertebrate and invertebrate animals, fungi, weed and marine threats.

Ideally research at all stages of the curve would be funded through the federal government’s National Environmental Research Program (NESP). NESP’s research themes for 2021-2027 were announced in March: resilient landscapes, marine and coastal, sustainable communities and waste, and climate systems. Feral animal and invasive species impacts will be addressed specifically as part of the resilient landscapes theme.

Marine pests are notoriously hard to eradicate once they establish in Australia’s marine environment, so research focused on prevention is essential. This could include studies that more precisely identify the arrival pathways of contaminated ships or untreated ballast waters that will help with measures to ensure those pathways are cleaned.

Research into containment can help slow or halt the spread of an invasive species. The six species of feral deer established in Australia that presently cover less than 10% of the country are projected to spread out across the entire mainland continent. Research is needed to better model this invasion process and improve the control techniques needed to contain the spread of feral deer and avert a major transformation of native vegetation from deer grazing.

Social research is important to advance property-level control efforts for emerging widespread pests and weeds. We need a good understanding of what motivates busy land managers for education programs to be effective.

Ultimately, our ability to protect Australia’s unique environments into the future will rely on our capacity to combat invasive species at all stages of the invasion curve.

More info

Applications for proposals to lead one of the four hubs under the redesigned National Environment Science Program can be submitted until the 30 June 2020. For more information on how to apply, visit the Australian Government’s Community Grants Hub.