A snapshot of our work

Jack Gough CEO

A snapshot of our work

Andrew Cox, CEO

Invasive species: What is the issue?

By Tim Low, Invasive Species Council co-founder, ecologist and author

Australia’s extinction record makes that clear. According to a 2019 journal article, 15 animals have been lost since 1960 and 12 of those extinctions can be blamed mainly on invasive animals and pathogens. The invasive species responsible include wolf snakes, chytrid fungus, foxes and cats.

That article was produced by the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, a consortium of universities and other bodies coordinating research in this area. It reviewed all of Australia’s animal and plant extinctions since European arrival to conclude that 43 extinctions were caused mainly by invasive species (including diseases), 31 by habitat loss, and 10 by all other impacts combined.

Species capable of causing extinctions keep entering Australia. Chytrid fungus arrived in the 1970s, wolf snakes in 1987, red imported fire ants in about 2000, myrtle rust in 2010. Three plant species are now critically endangered from the rust.

Extinctions are only one form of loss. Wherever invasive species swamp landscapes we lose something of the very essence of Australia.

The waters between Tasmania and Sydney now have stretches of seafloor dominated by New Zealand screw shells (Maoricolpus roseus) living at densities of up to several hundred per square metre, at depths of up to 80 metres.

Invasive ants, including yellow crazy ants in the Wet Tropics, are forming vast super colonies in which they eliminate other insects.

Weeds dominate vast areas, including mimosa, a prickly invasive shrub now in possession of more than 140,000 hectares of grasslands and wetlands on 15 river systems and 3 islands. Four rangers are employed in Kakadu National Park to keep it out. Other weeds include invasive pasture grasses fuelling hotter fires that by killing trees in many places are worsening the impacts of climate change.

As you can see, the continued impacts of invasive species are devastating and the work to tackle this issue is huge. That why the Invasive Species Council was founded by myself and 7 others in 2002. The organisation is determined to lessen the impact of these invaders, and couldn’t do this work without its dedicated supporters. Thank you so much for being an important part of our community, fighting for our wonderful, unique country.

The invasion curve, explained

To explain how the issue of invasive species can be tackled effectively, the Invasive Species Council uses the invasion curve – a graph of the invasion process depicting the rising harm and costs as an exotic species becomes established and spreads within its new environment.

After a new species establishes, there may be a period of days, months or even decades during which it is possible to eradicate it – before it becomes too widespread. If a species can’t be totally removed, it may still be possible to contain it, to prevent it spreading to the rest of its potential habitat across Australia.

Invasive species is a wicked problem. Here are some of the urgent projects we have been working on recently that speak to each stage of this invasion curve:

Prevention and early action: Yellow crazy ants

Yellow crazy ants are one of the world’s worst invasive species — they do not bite, but spray formic acid to blind and kill their prey. Once the ants reach super colony levels they can become a severe threat to people, especially children and the elderly, as well as pets. They can damage household electrical appliances and wiring.

Funded by the John T Reid Charitable Trusts and a Queensland Government sustainability grant, the Invasive Species Council provided two part-time staff to bolster control efforts by the Townville City Council. From June 2018 to December 2020 our team – together with a dedicated group of volunteers – undertook regular ant treatment and monitoring at Nome and other sites.

“Initially the ants were everywhere,” our assistant community coordinator Janet Cross remembers. “They were injuring – and sometimes even killing – animals like kangaroos, dogs and chooks.”

Eradication: Smooth newt

In 2013 Australia’s governments decided they would not attempt to eradicate smooth newts, which had recently established in waterways in Melbourne’s south-eastern waterways, probably after being abandoned as an illegal pet. In failing to take action, our governments were embarking on a dangerous ecological experiment – allowing salamanders, a completely new order of amphibians to this country, to remain in the wild and spread.

Because smooth newts are so different from anything Australian species have encountered before, the potential impacts are hard to predict. But the fact that smooth newts are prolific breeders, have a broad diet and can inhabit many types of habitats is a great cause for concern. They are likely to compete for food and habitat with native frogs and fish, and are potentially carriers of chytrid fungus, which has decimated frog populations in Australia.

Containment: Feral deer

Our landmark report, Feral Deer Control: A Strategy for Tasmania, was released in August 2021 and identifies a clear pathway for how Tasmania can apply a biosecurity-focused approach to the management of feral deer and provides steps to remove deer from all but the traditional deer range where they were found many decades before.

In November 2021, due to our strategy and resulting pressure, the Tasmanian Government released its own draft deer management plan. While this plan set aside areas for deer eradication and acknowledged that this issue cannot be managed by hunters alone, it falls well short of solving this issue – having no mention of environmental impact, no targets, no measurements, no timeline and no budget commitment. Most disturbing, it endorses the retention of feral deer in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area.

Management: Cats and foxes

At least 33 Australian mammal species are extinct – the worst mammal extinction record in the world – 24 mainly because of feral cats and foxes. And they continue to imperil hundreds of other native species. After the 2020 bushfires, organisations including the Invasive Species Council called for a concerted focus on feral animal control.

In fire-denuded landscapes feral cats and foxes can easily pick off small animals struggling to find food and shelter, and feral herbivores such as deer often stymie plant regeneration. We called for aerial control programs targeting feral deer, pigs and goats, and a fast-tracked cat trapping and fox baiting program at threatened mammal sites. In mid-2021, a national feral cat and fox coordinator was appointed to help drive cat and fox control action in bushfire affected areas.

The Invasive Species Council was influential in a 2020 federal parliamentary inquiry into feral cats, particularly in generating recommendations for prioritising action on feral cats, strengthening national threat abatement processes and establishing more cat-free havens on islands.

Since 2013 the Invasive Species Council has been a member of the national feral cat taskforce, overseeing threat abatement action on feral cats. The focus on feral cats has mobilised effort across the country, resulted in new control tools and shifted the national debate so that the general public now better accepts the need to control feral and domestic cats.

We have worked with several of Australia’s leading researchers to identify ways to better protect threatened species from feral cats and foxes:

- Undertake island eradications: Remove cats from islands with high biodiversity values (e.g. breeding seabirds) or where islands can serve as havens for species threatened by cats.

- Prepare for future major bushfires: Be prepared to rapidly install temporary shelters and control measures to protect surviving wildlife from predation by cats and foxes.

- Provide more control tools: Ensure land managers gain access to effective tools to control cats and foxes and support research to develop new control methods.

- Remove legal barriers: Apply standardised rules across Australia that designate feral cats as pests, reduce red-tape preventing the use of traps and toxins and require mandatory domestic cat desexing, microchipping and containment.

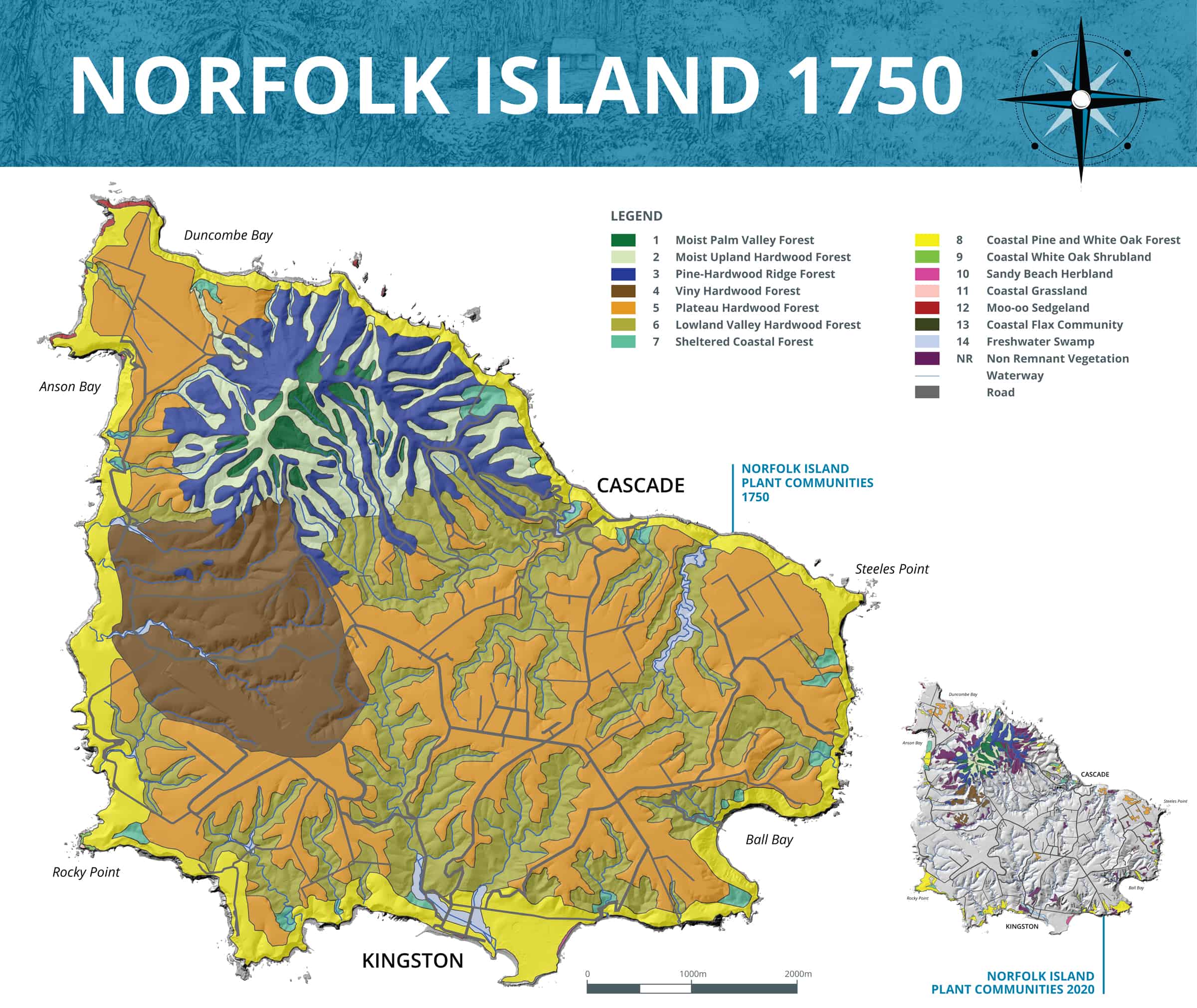

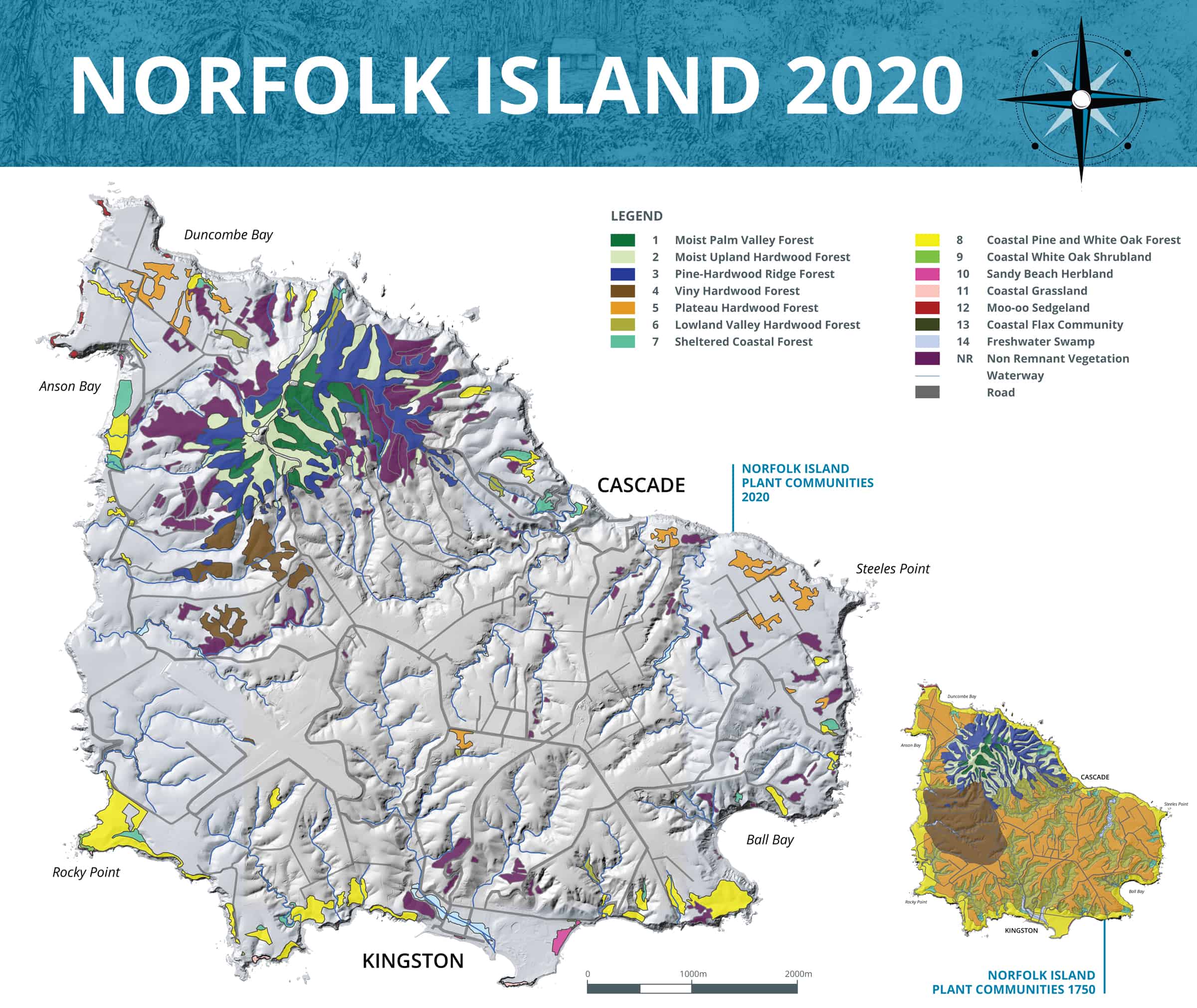

Ground-breaking project first step to restoring Norfolk Island

Over two years, we worked with local and mainland experts to create digital maps of what Norfolk Island’s forests, woodlands and grasslands looked like before Europeans arrived on the island and what that landscape looks like now.

These new maps will play a vital role in helping the island community restore its rich natural heritage and secure a future for many threatened native plants and animals.

The Invasive Species Council’s work is far from done.

Right now, invasive animals, weeds and diseases are Australia’s highest impact threat to native species – higher than any other environmental threat.

The Invasive Species Council is Australia’s only environmental organisation dedicated to strategically tackling this issue and has a strong track record of successfully campaigning for action to safeguards our environment from invasive species

We have the solutions, powerful alliances and a willing federal government.

What we need now is continued investment from the philanthropic community to catalyse strong, collaborative biosecurity to protect and restore what makes Australia extraordinary – our unique wildlife and habitats.