Eight years ago, one of the Invasive Species Council’s co-founders, author and biologist Tim Low, joined the Australian Wildlife Conservancy for annual monitoring at one of their reserves in the northern Kimberley, WA. The native wildlife Tim saw was something most of us today wouldn’t even recognise.

‘It was just mind boggling really. It was just overwhelming,’ Tim recalled in one of our recent Aliens Among Us webinars.

‘There was one trap. … I went there just after dusk and there was a Kimberley rock rat inside, so we let that go. A couple of hours later there was something else. It was a quoll, a northern quoll was inside. So we let that go. And I came back early the next morning and there was a scaly-tailed possum inside.’

‘It was just staggering. Three really high quality species of mammal inside one trap in one night. I’ve done lots of mammal surveys across Australia. I’ve never seen anything like that!’

Tim isn’t alone. Most Australians have never seen anything like that. We’ve lost the memory of what this age-old continent is supposed to look like, sound like and feel like.

A melting pot of threats including, of course, invasive species, are driving Australia’s wildlife into extinction.

Cats alone have substantially contributed to the extinction of 28 of our native animals, including the Yallara (lesser bilby) and the paradise parrot. Both are now lost forever.

But at places like the reserve Tim visited, feral cats and foxes are managed so their numbers are relatively low compared to the vast majority of Australia. These places give us a tantalising glimpse into how alive our landscapes can be when we free them from the pressure of introduced predators.

We are lowering cat numbers across new areas by helping local land managers deploy Thylation’s innovative cat control devices called Felixers. The latest versions which we have deployed use machine learning to differentiate between feral cats and native animals and target feral cats with very high target specificity.

With the help of an expert committee we have chosen five areas across Australia to deploy Felixers. The Invasive Species Council offered a total of ten Felixers to these site managers (two in each site) thanks to the support of a generous donor.

Reinforcing roosting sites for night parrots in Ngururrpa Indigenous Protected Area, WA

Once thought extinct until its dramatic rediscovery in 2013, the night parrot remains one of Australia’s rarest birds. They roost on the ground in hummocks of spinifex grass, making them particularly vulnerable to introduced predators – especially when immature birds hidden inside those roosts become very vocal in the days leading up to their first flight.

At the Ngururrpa Indigenous Protected Area in eastern WA, the dry sandplains and dunefields are home to 12 sites used by these elusive endangered parrots. Five of the sites are thought to be permanent roosts. The feral cats and occasional fox prowling around the night parrot roosting sites are believed to be one of the major barriers to their survival.

To protect the roosts, we’ve provided two Felixers to local Indigenous rangers to deploy around the night parrot roosts. The software on board the Felixers will selectively target cats and foxes that pass by the trap with a toxic gel that gets groomed off later by the cat, causing it to ingest the poison. All while avoiding native animals like the local night parrots.

Watch

Conserving Kyloring (western ground parrots) in Waychinicup National Park, WA

Another of Australia’s plump parrots with an affinity for the ground, Kyloring numbers are thought to be dwindling at around 150 birds.

In partnership with BirdLife Australia and Friends of the Western Ground Parrot, we’re supporting efforts to establish a second Kyloring population in WA’s Waychinicup National park – Manypeaks area. We have provided two Felixers to control feral cats in this new area to help the critically endangered parrots recover.

Protecting potoroos on Lungtalanana Island (Clarke Island), Tasmania

Lungtalanana (Clarke Island) covers an area of 82 km2 and is located close to the northeast coast of Lutruwita/Tasmania. The island was handed back to the Traditional Owners in 2005 and is now managed by the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre.

The island has been on a decades long journey of healing. Grazing livestock have been removed from the land, vegetation is being restored and cultural burning returned. But almost all of the native mammals that used to call Lungtalanana home are still missing, wiped out by invasive species, hunting and fires.

Now it’s time to return them. The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre has set out a vision of reintroducing Bass Strait Island wombats, long-nosed potoroos, Bennett’s wallabies, dunnarts and antechinuses. But the feral cats that drove many of them locally extinct are still a looming presence. We are working with the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre by providing a pair of Felixers to create a safe home for native mammals on Lungtalanana.

Saving species in Nyangurmarta Warrarn Indigenous Protected Area (Great Sandy Desert, WA)

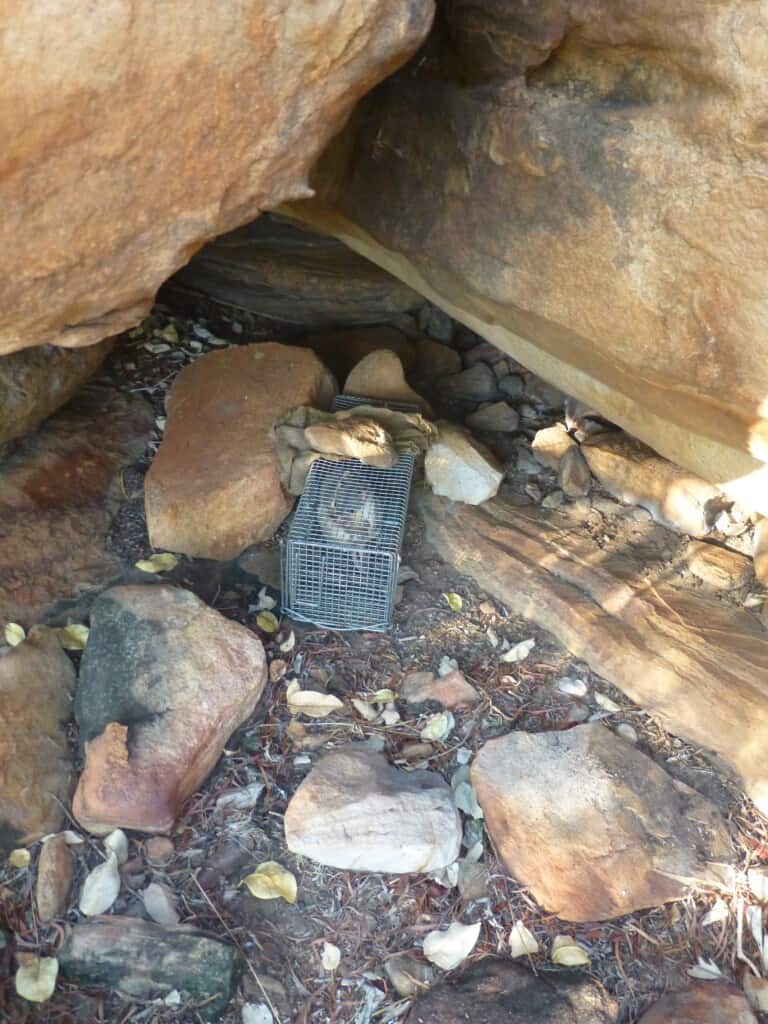

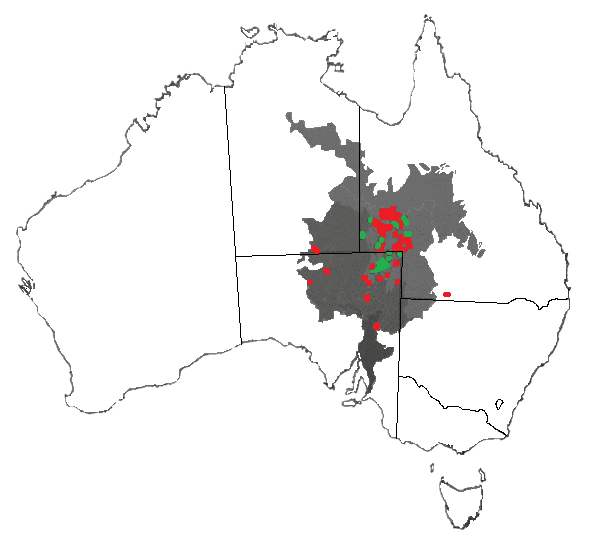

Threatened black-flanked rock wallabies (Petrogale lateralis)/Wiliji, northern quolls (Dasyurus hallucatus), brush-tailed possums (Trichosurus arnhemensis) and greater bilbies (Macrotis lagotis) all have a few things in common. They are all found in the Nyangumarta Warrarn Indigenous Protected Area in WA’s Great Sandy Desert, they all usually prefer living in rocky outcrops with cave systems, they all have relatively small ranges and they all fall within the critical weight range (35-5500g) for native animals most susceptible to predation by feral cats and foxes.

Unfortunately, this combination makes them easy to find for feral cats. But it also means if you can control feral cats in those small, discrete habitats then you can deliver major conservation benefits.

Keeping kowari safe at the Arid Recovery Reserve, SA

Kowaris are a small, relatively unknown marsupial “micro-carnivore” – another native struggling to survive predation by feral cats and foxes. They have lost enormous expanses of their natural range and were recently assessed as having a 20% chance of extinction within 20 years.

To safeguard the species, the Arid Recovery reserve in South Australia has translocated some kowaris behind the fences of its predator-free area.

But juvenile kowaris are small enough to pass through the fences. Once outside, they are under acute threat from feral cats and foxes that patrol the edges of the reserve in high numbers. Arid Recovery is already conducting year-round integrated pest management for 10 kilometres around the boundary of the reserve, so we are bolstering their efforts by supplying two Felixers to help protect young kowaris against feral cats.

These Felixers outside Arid Recovery are already up and running. Early reports showed feral cats were successfully being removed. They also picked up heartening photos of native bilbies, burrowing bettongs and re-introduced chuditch (western quolls)!

Scratching the surface

Of course, while Felixers will hopefully deliver much needed relief to these select local ecosystems, feral cats are a continent-wide problem.

Targeted efforts need to be backed-up with landscape-level management of feral cats by our state and territory governments. The federal government also needs to fix Australia’s deeply flawed environment laws so the impacts of feral cats are tackled with the resources and attention our native wildlife desperately needs – something you can help with right now.