Every five years, the Australian Government is supposed to release a State of the Environment Report, a lengthy report card that pulls together everything we know about how our environment is faring and the direction it’s heading in. We were slated to receive the latest edition in 2021, but the previous administration chose to lock it away until after the 2022 Federal Election in May.

The newly elected Labor government committed to releasing this report during the election campaign, and made good on that commitment last week.

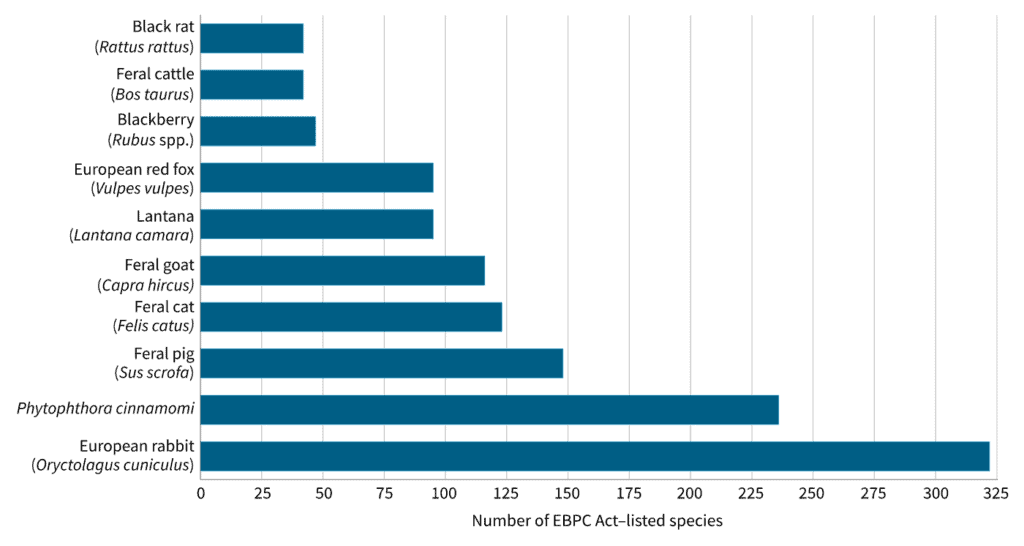

The report is over 2,500 pages long, packed with information that we will be busy pouring through for many weeks to come. A full 16 of those pages are dedicated to the threat of invasive species in the Biodiversity chapter alone, more than any other threat. But here’s a much shorter summary of what we’ve found so far.

The good:

- This year was the first time Indigenous Australians co-authored the report. It rightly emphasises the connection between the wellbeing of Country and the wellbeing of people by tapping into tens of thousands of years of deep knowledge.

- Citizen science has rapidly increased, resulting in improved observations of the environment and more data that, in turn, supports more effective management.

- For the first time, the conservation status of an Australian species — the eastern barred bandicoot — was reclassified from extinct in the wild to endangered. This was thanks to three decades of captive breeding and releases in seven pest-free enclosures and islands.

The bad:

- Every category of the Australian environment, except for urban areas, have deteriorated since 2016. Climate change, habitat loss, invasive species, pollution and resource extraction are causing rapid environmental declines and increasing the number of threatened species.

- Since 2016, two species have been officially declared extinct — the Christmas Island pipistrelle (due to predation by invasive species) and the Bramble Cay melomys (due to the impacts of climate change). In addition, large areas of central and northern Australia have experienced declines in crucial Melaleuca wetlands and billabongs due to feral water buffalo, pigs and cattle.

- Invasive species were again identified as the most prevalent threat to Australian wildlife and are the primary cause of extinction events since colonisation.

- There are more non-native plant species than native plant species in Australia.

- Australia has had more modern mammal extinctions than any other continent.

The disappointing:

- Australia’s investment in conserving our environment is not up to the challenge. The 2021 State of the Environment Report confirmed what we published in our recent Averting Extinctions report, that the funding allocated to our environment is a shrinking fraction of what it needs to be. Our report found the amount we spend per nationally listed threatened species is less than a tenth than what the US Government spends.

- There was little to no mention of how effective biosecurity is at protecting our environment and way of life. The invasion curve shows us how much cheaper and more effective it is to prevent new invasive species, or eradicate newly arrived invaders, than it is to deal with an invasive species that has established and spread to the point where eradication is no longer feasible. Australia’s biosecurity system is in desperate need of strengthening, and that’s why we’re campaigning so hard for the Decade of Biosecurity.

- The report overview concludes invasive species management is ‘a huge challenge that is currently beyond the resources available’. We disagree, and believe statements like this send the wrong message. Australians across the country are proving each and every day how we can successfully manage invasive species. The Wet Tropics Management Authority in Cairns is seeing positive results from its yellow crazy ant eradication program, the Lord Howe Island Board achieved the world’s first eradication of myrtle rust in 2018, private conservation groups releasing captive-bred eastern barred bandicoots into feral predator-free areas were behind them recently being taken off the extinct in the wild list, and organisations like Gamba Grass Roots are spurring broadscale community buy-in to control some of Australia’s worst weeds. Invasive species management is as possible as it is necessary. What we’re missing is the political will from federal, state, territory and local governments to provide the policies and investments that make successful invasive species management commonplace.

The 2021 State of the Environment Report makes for incredibly grim reading. But its two big lessons are that it’s not too late and that Australia’s native wildlife can’t afford us throwing invasive species management into the “too hard basket”.

This report needs to spark urgent change. We need vastly more investment in our environment, we need a major overhaul to Australia’s environmental policy and we need to support decisive action on the invasive species. Most of all, we will need your support to make all of this happen.

More info: