Hawaii, Lord Howe Island, myrtle rust and green iguanas featured in the fifth Island Arks Symposium held last October in Fiji.

This two-yearly gathering organised by Wild Mob brings together conservation researchers, indigenous owners, managers and advocates, many of them working on invasive species issues.

This is the number one priority for conservation on Pacific islands because, as David Moverley, Invasive Species Adviser of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme reminded us, invasive species are the primary extinction driver for single-island endemics in the Pacific. Invasive species are poorly managed and the situation is deteriorating.

Invasive species are like a living form of pollution but much harder to prevent and recover from, said Randy Thaman, Emeritus Professor of Pacific Islands Biogeography, at The University of the South Pacific. While pollution impacts diminish in time once the source is stopped, those of invasive species increase over time.

Hawaii, epicentre of invasive species

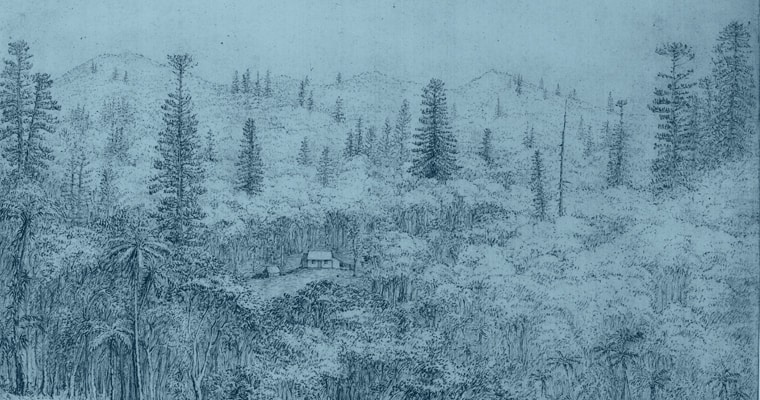

Hawaii is one of the world’s most invaded places and has lost two-thirds of its endemic bird species. Before European settlement 240 years ago, there were no land reptiles or amphibians – now there are 40 reptiles and six amphibians. There are also 417 new marine and estuarine species, 2500 introduced arthropods, and the number of bird species has doubled. One study found that one new plant disease or insect arrives with imported goods each day. Only 50% of native habitat remains, and its future is precarious due to invasive species and climate change.

Conservation organisations are working together on many invasive species projects. One major collaborator is the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit at the University of Hawaii. It has supported public and private landowner partnerships organised along watersheds (similar to the traditional “ahu`pua`a” system of cooperation for protecting resources and producing food) to combat feral animals such as goats, deer and pigs, and helping with invasive ant and weed control. It runs “Spot the Ant Month”, mobilising the community to report electric ants.

An insidious new disease on Hawaii has killed hundreds of thousands of the state’s most important tree, the ‘ōhi’a lehua, which are the backbone of forests covering almost half a million hectares. Called Rapid ‘Ōhi’a Death, the disease is caused by two previously undescribed species of Ceratocystis thought to come from Asia and Central America. Trees can be infested for months before they show symptoms.

Strict quarantine has been established in an effort to contain the disease while researchers seek to understand it. Australia and other Pacific nations also urgently need to understand more about the disease, as it may pose a threat to other myrtle plants.

Myrtle rust focus

Last year’s arrival of myrtle rust in New Zealand precipitated a symposium session devoted to the issue.

The New Zealand response to an incursion detected in 2017 stands in stark contrast to Australia’s response in 2010, which was described by one presenter as ‘a case study of how to get a biosecurity response wrong’.

In Australia, as the rust spreads, we are still learning how many of the 2288 native Myrtaceae will be affected. So far, 15% of species have proved susceptible, and two species have been nominated for critically endangered listing. Fortunately, myrtle rust has not reached the southwest corner, Australia’s Myrtaceae diversity hotspot.

In New Zealand, myrtle rust was detected in April 2017, infecting plants in a large area mostly on the north island. It is the same strain as the rust in Australia, likely to have arrived on strong easterly winds.

Because many potentially susceptible species are iconic to Māori and have historical significance as taonga (treasures), the response from the Maori community has been strong. The Māori Biosecurity Network, which led a large and enthusiastic delegation to the symposium, have organised regional meetings and publicised the issue, calling for greater involvement in biosecurity decision making.

An official said New Zealand has so far spent $40 million on myrtle rust eradication, including $3.5 million for research on susceptibility. Tragically, a $60,000 proposal in 2016 for preparatory research was knocked back by New Zealand’s primary industries department a year prior to the rust’s detection.

Eradication will be difficult. A decision on whether to continue to eradicate or to transition to containment and management will be made soon.

A joint Australian and New Zealand workshop to share myrtle rust research findings and response strategies took place in Canberra in December.

Lord Howe Island progress

Lord Howe Island, where there are determined efforts to remove many damaging invasive species and strengthen biosecurity, featured in five presentations. As an example of the legacy left by poor biosecurity in the past, in 1965, 40% of the island’s ant species were introduced; now it is 74%.

One of the worst of these ants, the super-colony-forming African big-headed ant, is in the final stages of eradication. If successful, it will be the most globally significant island eradication of an ant to date due to the size of the island and the complexity of the program.

Myrtle rust was eradicated after detection late last year. This was a relief, for Lord Howe Island has several endemic Myrtaceae. In a rare example of preparedness in Australia, response gear and treatment chemicals were pre-assembled and staff were trained. The rust was detected by an islander who had attended an awareness raising workshop the year before.

Sixty-eight weeds are subject to a 30-year eradication program that began in 2004. The island has been divided up into small blocks and grid searches are undertaken at least once every two years. Some species such as cherry guava and asparagus fern that once dominated large areas are now becoming rare.

All eyes will be on Lord Howe Island this year as rodent eradication is set to go in the middle of 2018.

Green iguanas on the rise

Fiji is in the early stages of invasion by the green iguana. While efforts to date have been slow and poorly coordinated, there are hopes eradication can still be achieved.

The green iguana is called the giant invasive iguana in Fiji to distinguish it from three smaller native green-coloured iguanas endemic to the country. These native iguanas are the only known species of their kind outside the Americas, and the Fijian crested iguana is listed by the IUCN as critically endangered due to habitat loss and invasive species.

The green iguana was first detected in 2000 on Qamea island in Fiji, not long after expatriates illegally imported some hatchlings. It has since been detected on two nearby smaller islands. Elsewhere, the green iguana has established on 12 Caribbean islands, Hawaii, the Canary Islands and Florida, where they have caused extensive damage. The governments of Florida, Cayman Island and Puerto Rico took 30 to 40 years to realise the extent of the problem, by which time eradication was no longer feasible.

In addition to competing with the endemic iguanas, based on impacts elsewhere, the green iguana in Fiji is expected to defoliate and kill trees, damage subsistence gardens and increase poverty, create a nuisance and health risk to tourists, and impact airfields, roads, seawalls, other infrastructure (either from nests undermining foundations or through aircraft and vehicle collisions) and nature-based tourism attractions.

National conservation group NatureFiji-MareqetiViti is coordinating a community program to build awareness, report iguana sightings and prevent their deliberate spread. The challenge is to convince villagers the iguana is a threat rather than a desirable novelty or pet. Detector dogs and reports from local villagers are used to locate lizards and their nests.

Working on the overwhelming

As Phil Andreozzi from the Department of Agriculture USA said, institutions are increasingly recognising the ‘agonisingly important’ issue of invasive species on Pacific islands. Instrumental in this is the Pacific Invasives Partnership, a coalition of governments, and research and conservation bodies conducting outreach and advocacy and incubating new ideas to improve biosecurity for Pacific Islands in the Oceania region.

The theory is that ‘people who have dinner and eat mangoes together’ will have good relationships that foster collaboration. The Invasive Species Council formally joined the partnership at the symposium.

The next symposium, Island Arks Symposium VI, will be held on Rottnest Island, Western Australia, on 11-15 Feb 2019.

More info

- Island Arks Symposium V, Fiji October 2017 (with presentations) >>

- Island Arks Symposium VI, Rottnest Is. WA February 2019 >>

Note: Input from Christy Martin, University of Hawai’i, is appreciated.