The Norfolk Island Vegetation Mapping Project has described and mapped 14 distinct native plant communities on Norfolk Island. This series of fact sheets presents information about each of the communities.

There are 180 native plant species, of which about 25 per cent are endemic, and a further 370 naturalised species on the Norfolk Island Group (Mills 2009). However, prior to 2020, there was no comprehensive, island-wide description or map of the native plant communities present.

The Norfolk Island Vegetation Mapping Project commenced in 2018 and sought to produce island-wide vegetation maps of Norfolk Island: one showing current native plant communities and another showing the native plant communities predicted to have been present in 1750.

A native plant community is a distinct association of native plants that grow together, as determined by environmental factors including moisture availability, maritime influence, aspect, prevailing winds and soil characteristics.

The 14 distinct native plant communities on Norfolk Island include forests, swamps, shrublands and grasslands.

Fact sheet 1: Moist Palm Valley Forest

Thick nee-ow palm and tree fern forest mostly in mountain valleys.

This community occurs in the deep valleys on the mountains, almost entirely within the Norfolk Island National Park. It occurs primarily on the moister, southern side of the mountain, and historically may have extended down to deep lower valleys.

This community is usually a dense stand of nee-ow palm (Rhopalostylis baueri), also called Norfolk Island Palm, with the two tree ferns, smooth tree fern (Cyathea brownii) and rough tree fern (Cyathea australis ssp. norfolkensis), other fern species, and scattered hardwoods including pennantia (Pennantia endlicheri). At lower altitudes, on upper slopes and on the northern side of the mountains, hardwoods become more common.

Nee-ow palm can reach 10 metres in height and its bright-red fruit is one of the main foods of the endemic green parrot (Cyanorhamphus cookii).

Fact sheet 2: Moist Upland Hardwood Forest

Thick hardwood forest mostly in the Norfolk Island National Park.

This native plant community grows on the slopes of valleys around the mountains, between the Moist Palm Gully Forest and the Pine-Hardwood Ridge Forest communities.

The forest is relatively species-diverse, but generally lacks some species that occur at lower altitude and includes a few species that prefer higher (moister) altitudes. One of the key species, sharkwood, is a medium-sized tree with a distinctive strong garlic-like smell during the spring months. Flowers are yellow and the seeds form in capsules and are red when mature.

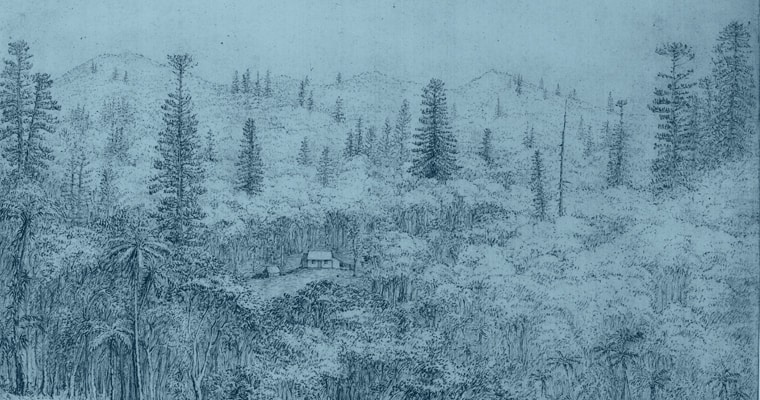

Fact sheet 3-Pine–Hardwood Ridge Forest

Tall pine forest on ridges, mostly in Norfolk Island National Park.

The ridges on the mountain flanks usually support many Norfolk pine (Araucaria heterophylla), a species largely excluded from the Moist Upland Hardwood Forest. The forest contains a number of other hardwood species.

The Norfolk pine is an easily recognised large pine that can grow to 60 metres. Cultivated around the world as an ornamental tree, its wood is used for construction, wood turning and crafts. The seeds are a popular food for the endemic and threatened green parrot.

Fact sheet 4: Viny Hardwood Forest

Thick rainforest with lots of Samson’s sinew vine in the Mission Road area.

This community occurs at a low altitude on the south-western flanks of the mountains and extends towards the coast. Remnants include the Botanic Gardens and some north of Mission Road. While most has been cleared, several key species appear to indicate its previous limits. The key indicator species are large old whitewood trees (Celtis paniculata) and the robust Samson’s sinew vine (Callerya australis).

Whitewood is a large and spectacular tree with white to grey trunks that are often buttressed at the base. Clusters of green flowers can be seen in summer, after which a small round fruit is produced.

The vine, Samson’s sinew, often appears as large woody coils hanging from the tops of trees. Its springtime flowers are cream-coloured, sometimes with a bluish tint. They are followed by thick bean-like velvety pods.

Fact sheet 5: Plateau Hardwood Forest

Mixed hardwood forest found on flat areas at Steeles Point and Anson Bay.

This community is the most widespread forest on the lower parts of the island and is found on level ground in the Steeles Point and Duncombe Bay area, but was probably once widespread including through burnt pine.

It is the drier version of the Upland Hardwood Forest. Norfolk Island pine (Araucaria heterophylla) may have been rather uncommon in this forest in the past.

Old and naturally occurring birdcatcher tree (Pisonia brunoniana) occurs in several places and may be indicative of this forest type. Originally, the understorey may have been quite open in places, supporting the shrub Norfolk evergreen (Alyxia gynopogon) and the hardier ferns.

White oak (Lagunaria patersonia) is a commonly occurring, large and spectacular tree growing to more than 20 metres. Its pink- and mauve-coloured flowers fade to white with age and have a waxy texture. The seed pods contain sharp hairs that can irritate the skin.

Fact sheet 6: Lowland Valley Hardwood Forest

Mixed hardwood forest found on flat areas at Steeles Point and Anson Bay.

This community is the most widespread forest on the lower parts of the island and is found on level ground in the Steeles Point and Duncombe Bay area, but was probably once widespread including through burnt pine.

It is the drier version of the Upland Hardwood Forest. Norfolk Island pine (Araucaria heterophylla) may have been rather uncommon in this forest in the past.

Old and naturally occurring birdcatcher tree (Pisonia brunoniana) occurs in several places and may be indicative of this forest type. Originally, the understorey may have been quite open in places, supporting the shrub Norfolk evergreen (Alyxia gynopogon) and the hardier ferns.

White oak (Lagunaria patersonia) is a commonly occurring, large and spectacular tree growing to more than 20 metres. Its pink- and mauve-coloured flowers fade to white with age and have a waxy texture. The seed pods contain sharp hairs that can irritate the skin.

Fact sheet 7: Sheltered Coastal Forest

Thick forest that only occurs close to the coast in areas protected from wind and salt. Small pockets remain at Bumboras, Ball Bay and Selwyn Reserve.

This forest is differentiated from Lowland Valley Hardwood Forest by its location in the lowest parts of lowland valleys, very close to the coast, where there is apparently a strong coastal influence. The coastal species in this community that largely do not occur in the Lowland Valley Hardwood Forest include the ferns King’s brackenfern (Pteris kingiana) and (Asplenium difforme) and the trees (Excoecaria agallocha) and (Pisonia brunoniana).

Ironwood (Nestegis apetala) is a small, relatively common tree, usually with wavy-edged leaves. Fruits are most often yellow, sometimes red or purple, and look like small olives.

Fact sheet 8: Coastal Pine and White Oak Forest

Hardy open forest of Norfolk Island pines and white oaks that can be seen at Hundred Acres.

This community once occurred along the entire coast around the island, and on Nepean Island. To some extent, it is the extension of the Pine Ridge Forest found on inland ridges, both being rather drier than the adjacent vegetation and with Araucaria heterophylla prominent.

Hardwoods are generally uncommon but often found in inland sheltered places. The understorey is often quite open, with remaining intact examples indicating a herbaceous ground cover with scattered shrubs. Near the southern coast melky tree (Excoecaria agallocha) may occur, and rare Norfolk Island euphorbia (Euphorbia norfolkiana) and coastal coprosma (Coprosma baueri) appear to favour this forest.

Fact sheet 9: Coastal White Oak Shrubland

Stunted, low growing white oaks and melky trees such as those near Cemetery Bay, Ball Bay and Hundred Acres.

Stunted shrubby white oak plants (Lagunaria patersonia) occur on very exposed coastal cliffs. This shrubland may have been quite common previously. The associated species are typical coastal species, including pigface (Carpobrotus glaucescens), native spinach (Tetragonia implexicoma) and Achyranthes aspera. The rare coastal coprosma (Coprosma baueri) is also sometimes found in this community and in the past may have been common.

Fact sheet 10: Sandy Beach Herbland

Low growing, non-woody plants growing in sand at Slaughter Bay, Anson Bay and Cemetery Bay.

The upper sandy beaches at Kingston and Anson Bay support typical sandy beach species. They include salt couch (Sporobolus virginicus), coastal spurge (Euphorbia obliqua), native vigna (Vigna marina), Canavalia rosea and club rush (Ficinia nodosa).

The creeping plant Calystegia soldanella, now probably extinct on the island, once occurred in this community.

Fact sheet 11: Coastal Grassland

Thick, salt tolerant grasses and sedges growing in sandy coastal areas.

Salt couch (Sporobolus virginicus) dominates many exposed coastal sites on sea cliffs.

Other species include pigface (Carpobrotus glaucescens), native spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides), chaff flower (Achyranthes aspera), yellow daisy (Senecio australis) and club rush (Ficinia nodosa).

Fact sheet 12: Moo-oo Sedgeland

Common on Phillip Island and the northern islets off Norfolk Island. Also present on the hot, exposed northern coastal slopes of Norfolk Island.

This is a sedgeland dominated by Moo-oo (Cyperus lucidus), which grows very densely, almost to the exclusion of other plants. This community covered large parts of Phillip island, as described by Phillip Gidley King.

Moo-oo is a robust perennial sedge. The stems are solid, triangular in cross-section and grow to 1.3m. The leaves, which all grow from the base of the stem to about 1m in length, are thick and glossy. The flowers, which individually are inconspicuous, form an attractive umbrella-like head which is bright red when young, turning red-brown as it matures. The fruit is a small, dark, angular nut.

Fact sheet 13: Coastal Flax Community

Coastal slopes with some protection, more common on the southern side of Norfolk Island, particularly where pines offer shade.

This community is somewhat speculative as little evidence remains of its original character and distribution. Although it was present by the time of the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1774, it is also not clear if the key species flax (Phromium tenax) is native to Norfolk Island. Dianella intermedia grows to 60cm with pale violet flowers followed by turquoise berries. Asplenium difforme is part of the spleenwort group of ferns and its fronds are thick and waxy to protect it from sea spray.

Fact sheet 14: Freshwater Swamp

Along watercourses, particularly in shallow, wide valleys. Was probably once much more widespread.

Prior to convict times, a large freshwater swamp existed across the Kingston Common. While that swamp is largely gone, a few swamps occur elsewhere on broad valley floors with a very low gradient and other similar valleys probably supported swamps prior to infilling caused by erosion after clearing of the surrounding forests.

These swamps would have been surrounded by dense forest. Today, many introduced species are also found in the wetland habitats.

Fact sheet 15: Native Plant Communities of Norfolk Island

There are 180 native plant species (of which about 25 per cent are endemic) and a further 370 naturalised species on the Norfolk Island Group (Mills 2009).

However, prior to 2020, there was no comprehensive, island-wide description or map of the native plant communities present. The Norfolk Island Vegetation Mapping Project commenced in 2018 and sought to produce island-wide vegetation maps of Norfolk Island: one showing current native plant communities and another showing the native plant communities predicted to have been present in 1750.

A native plant community is a distinct association of native plants that grow together, as determined by environmental factors including moisture availability, maritime influence, aspect, prevailing winds and soil characteristics. The 14 distinct native plant communities on Norfolk Island include forests, swamps, shrublands and grasslands.