The release of our report Norfolk Island: Protecting an Ocean Jewel sets a path for reversing the decline of many threatened species on the island, eradicating harmful invaders and improving the Norfolk Island’s appeal as a nature-tourism destination.

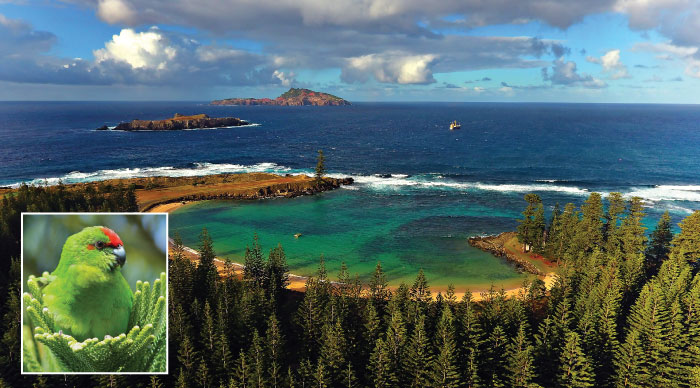

Norfolk Island emerged from the southern Pacific Ocean as a volcano 3 million years ago, far from any other landmass. What remains of the eroded core remnants are isolated, biologically, socially and politically.

In common with islands elsewhere, the biological isolation has given rise to highly endemic flora and fauna – plants and animals found nowhere else in the world – but they are susceptible to decline when the isolation is breeched by humans and human-introduced species. Polynesians temporarily arrived perhaps 800 years ago, then Europeans exploited and settled the island over the past two centuries.

The tumultuous history of convicts, mutineers and settlers since has had a massive impact on the biology of these islands, mainly due to extensive clearing and the introduction of species from other parts of the world.

For much of the islands’ recent history there has been a major effort to repair the damage and protect the much-depleted indigenous wildlife.

Of the 15 species of subspecies of endemic land birds present at European settlement, six are extinct, two are critically endangered and two are vulnerable to extinction. The two native bats are locally extinct, the local skink and gecko is lost from Norfolk Island but remains on Phillip Island and far away Lord Howe Island.

The island has 46 plant species listed nationally as threatened, 30 of these are found nowhere else on Earth.

It is home to the critically endangered Norfolk Island green parrot (or parakeet), which has the ‘dubious honour of having to be rescued from the brink of extinction not once, but twice’.

Norfolk and Nepean Islands are listed by Birdlife Australia as an Important Bird Area (among Earth’s most exceptional places for birds) for supporting the entire populations of the white-chested white-eye (Zosterops albogularis), slender-billed white-eye (Zosterops tenuirostris), green parrot (Cyanoramphus cookii) and Norfolk gerygone (Gerygone modesta), as well as more than 1% of the world populations of wedge-tailed shearwater and red-tailed tropic bird.

Biosecurity

When Norfolk Island lost self-governance on 1 July 2016, the Australian Government assumed responsibility for pre-border and border biosecurity. A regional council was established that included in its functions the management of on-island pests and weeds using the held-over Norfolk Island laws. This is a temporary arrangement while new biosecurity laws, probably based on NSW laws, are put in place.

Biosecurity for Norfolk Island to date is extremely challenging and its success or failure will determine the fate of its exceptional wildlife.

Today there is no harmonised biosecurity regime in place, there is insufficient priority accorded to environmental biosecurity despite the economic potential of nature tourism, and the resources available for biosecurity remain constrained while risks continue to grow.

There is the potential for Norfolk Island to be an exemplar in conservation-based island biosecurity. In our report, Norfolk Island: Protecting an Ocean Jewel, we make 25 recommendations to set Norfolk on that exemplary path.

Measures include harmonised biosecurity arrangements, improved industry and community engagement, completion of a risks and pathways analysis, creation of a biosecurity strategy and declaration of Norfolk Island as a biosecurity zone under NSW biosecurity laws and as an NRM region of Australia.

Also needed are improved preparations for new incursions, an ongoing commitment to eradicate Argentine ants, and programs to eradicate other harmful plants and animals, where this is feasible and acceptable.

Finally, greater cooperation with other island managers from Australia and New Zealand, and a new islands unit within the Australian Government will advance the special interests of Norfolk Island and other oceanic islands.

Funding for this work was provided by the Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation (Eldon & Anne Foote Trust Donor Advised Program 2016) and the Packard Foundation.

More info