On paper Australia appears ready to respond to dangerous new invasive species, but dig a little deeper and our defences start to look paper thin.

NEBRA, Australia’s National Environmental Biosecurity Response Agreement, is an important document endorsed by federal, state and territory governments. If an invasive species becomes established in Australia for the first time, it is this agreement that outlines steps for deciding whether to jointly fund its eradication, or not.

Prior to the agreement, decision-making was ad hoc.

To eradicate a new invasive species a rapid response is essential. A clear process and the ability to quickly mobilise funding and resources from up to nine jurisdictions – the federal government and each state and territory government likely to be affected if eradication is not successful – saves valuable time.

Response agreements have supported the agricultural sector for many years: since 2002, the Emergency Animal Disease Response Agreement for responding to outbreaks of livestock diseases such as foot and mouth disease, and since 2005 the Emergency Plant Pest Response Deed for incursions impacting on horticultural and other plant-based industries.

NEBRA arrived in 2012. It was modelled on the animal and plant industry agreements, and negotiated without consulting environmental stakeholders. Last year, consulting firm KPMG conducted a five-year review of NEBRA. Public comments were sought. This was the first time the agreement had been subject to community input.

A secret agreement

It was difficult to find out how NEBRA had been operating, since public information is only made available after a decision is made to fund an eradication.

The discussion paper for the review shed little light, so the Invasive Species Council asked for a list of all responses considered under NEBRA. We were verbally provided with a list of two (in addition to the funded responses).

We had accidentally learnt of another new invader through a chance conversation with a government official. A smooth newt (a salamander) had been found in Melbourne’s south-eastern suburbs. This was not public knowledge, and we only found out a year after it was decided to do nothing. It took us many more months and a freedom of information application to piece together the reasons.

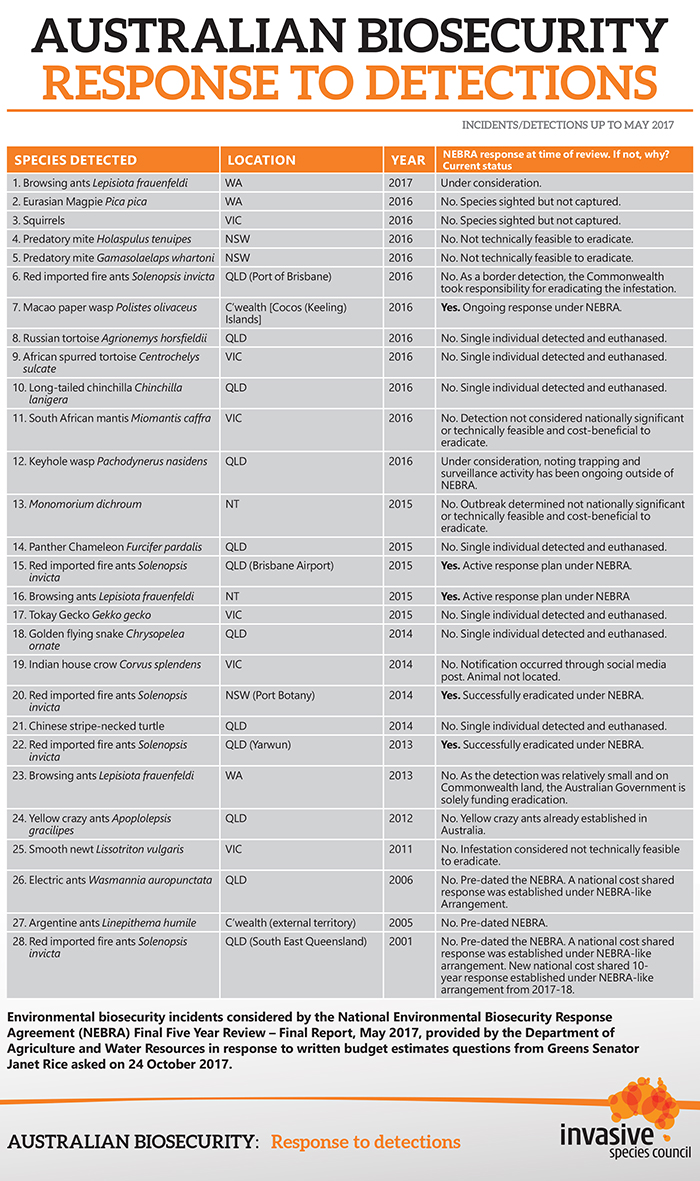

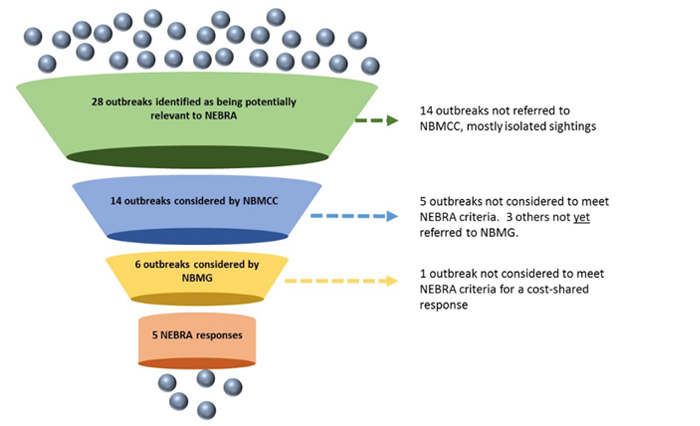

We have since learned from the final report released at the conclusion of the review that 28 outbreaks have been considered. In only five cases was the agreement triggered, three of these for red fire ants.

Through questions in Parliament we now have information about the full list of 28 outbreaks (see list below or download as a pdf). In February we submitted a freedom of information request for more detail.

KPMG review calls for mature, transparent agreement

KPMG delivered its review in May 2017, recommending that as part of a ‘maturing NEBRA’ there should be greater transparency and public communication. It flagged a stronger role for the federal environment department and proposed that formal consultation be required with environmental agencies in each state and territory. At present, officers from agricultural departments are the main decision-makers under NEBRA, and may or may not consult with environmental colleagues.

The review noted a lack of coordinated preparedness for environmental responses, unlike the standing arrangements led by purpose-made bodies for the agricultural sector, Animal Health Australia and Plant Health Australia. It proposed that ‘continuity of oversight’, ‘feedback on operations and custodianship’ and ‘testing of communication’ could occur by establishing a standing body of federal, state and territory officials. It recommended that a Chief Environmental Biosecurity Officer, a role proposed by the national biosecurity review, should lead NEBRA responses if such a position was established.

The review supported timely reporting of all decisions, whether NEBRA is triggered or not. It recommended changes to decision-making, including to the national significance test and a simplification of the benefit-cost requirement. The current benefit-cost test applied for decisions under NEBRA is too onerous for assessing environmental invaders.

The review found that eight incursions (29% of all incursions) were not formally referred to the national biosecurity management group for a decision, a breach of NEBRA procedures.

Identifying an important gap, the review proposed that in some circumstances containment rather than eradication should be funded under NEBRA. This could be applied to plant diseases like myrtle rust, a marine pest or a weed where containment in one part of Australia could prevent it spreading to other states.

An environment-centric response agreement

Our submission to the review process went much further. It outlined the major differences between responding to incursions that impact on an agricultural industry and the environment. An environment-centric response agreement would have more defined thresholds of feasibility and significance, be automatically triggered for known priority pests, apply the precautionary principle and use majority rather than consensus-based decision-making. Environmental stakeholders would be invited as observers to technical and management meetings.

Environmental incursions commonly have high levels of uncertainty which would normally rule out a NEBRA response or result in lengthy delays. We recommended that in some cases an eradication should proceed for a trial period while techniques are tested or developed.

Unlike the review process, we used examples to demonstrate NEBRA deficiencies. Our examples included the red fire ant, smooth newt, myrtle rust, Asian honeybee and the weed Koster’s curse.

To improve transparency, we called for reasons for all NEBRA decisions to be published and for an independent review to be conducted after each outbreak. In all we made 23 recommendations, eight of which were taken up in part by the review recommendations.

Expanded industry carve outs

Due to the hierarchy of the response agreements, if a new invasive species has both agricultural and environmental consequences, the animal or plant industry response agreement is triggered instead of NEBRA. Environmental consequences are given lower priority. The affected industry has decision-making (including veto) powers. We saw this with the industry-focused response to the 2010 myrtle rust outbreak.

This situation will be exacerbated with two new industry-based agreements currently in development for agricultural weeds and aquaculture. NEBRA will also be subservient to these, even where a potential weed or marine pest covered by each of these agreements has major environmental consequences.

The Invasive Species Council is not aware of any attempt to consult with environmental non-government interests regarding either of these agreements and our requests to be involved with the aquaculture agreement have been refused.

This makes it even more critical for the recommendations of the NEBRA review to be applied to all other response agreements. The involvement of industry in decision-making (and its contribution of funds) should not be permitted to diminish consideration of the public interest in protecting the natural environment.

A new NEBRA

A revised NEBRA is due to be considered by the National Biosecurity Committee in late 2018. The federal Department of Agriculture and Water Resources informed the November 2017 environmental biosecurity roundtable that there will be consultation on the government’s response to the KPMG review in early 2018.