Author and biologist Tim Low was one of the Invasive Species Council’s co-founders 20 years ago. He wrote and published some of the earliest issues of Feral Heralds, and brings us another story in this edition.

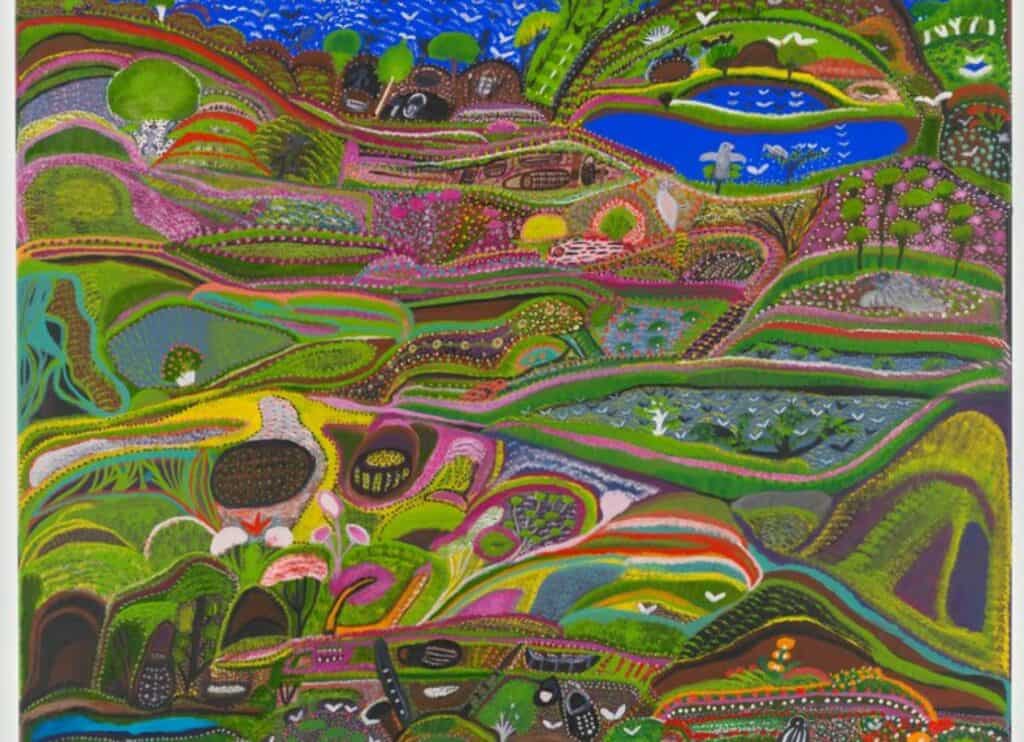

A stand-out feature of the recent Australian 2021 State of the Environment report was the strong input of Indigenous authors. Most chapters had Indigenous co-authors, and there was an Indigenous chapter for the first time ever, outlining Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander notions of Country (or Ailan Kastom) and the barriers to better caring for Country.

Some academics have claimed that Indigenous people welcome introduced species and do not want them controlled. British geographer Charles Warren asserted recently that ‘Australian Aboriginal people regard many introduced species as valuable and “belonging” … and New Zealand’s “Predator Free 2050” campaign conflicts with Maori cultural beliefs.’

Australian anthropologist David Trigger posed a question: ‘If ‘Indigenous Australians’ make intellectual room for non-native species, recognizing their capacity to achieve a place in the environment and the nation, does this confound (or at the least complicate) scientific or eco-nationalist messages that position introduced species as “alien”?’

Australian sociologist Adrian Franklin went much further by celebrating feral animals in his 2006 book Animal Nation. ‘We should not be merely surprised by Aboriginal people’s largely positive view of feral animals’, he wrote, ‘we should also be inspired and perhaps a little ashamed.’ His chapter on this topic ends with a plea: ‘Rather, without in any way altering our concern for native animals, we might finally concede that the ferals are as Australian as we are, that we all, after a while, belong to country.’

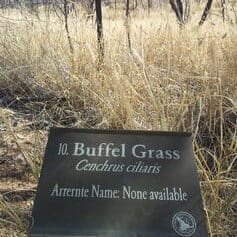

The Indigenous chapter of the 2021 State of the Environment Report can’t be reconciled with these comments. The very first paragraph about biodiversity is clear that ‘Biodiversity and the health of Country has been impacted by invasive species and climate change, which threaten the number of native species and the health of the land.’ This chapter mentions cane toads killing reptiles, buffel grass claiming large areas of the Northern Territory where it interferes with fire practices and sacred sites, and feral pigs, buffalo and weeds threatening Kakadu’s wetlands. This chapter had as its lead authors Wuthathi woman Terri Janke and Barkandji woman Zena Cumpston.

Franklin claimed that camels, donkeys and horses ‘do not present themselves as pests to Aboriginal people’, but the Indigenous chapter says feral camels are ‘threatening waterholes and cultural landscapes across the deserts’.

The three academics I cited believe that concerns about invasive species are overstated and coloured by prejudice against that which is foreign. Franklin backed his claims about Indigenous people by quoting from a 1995 report produced for the Central Land Council by Bruce Rose, a biologist who interviewed hundreds of people in central Australia. Rose wrote this:

‘The effects of feral animals on the country are not seen as a cause for concern. It is seen as a natural phenomenon that animals eat the grass and raise a bit of dust. To separate the impact of feral animals from native species on these grounds is not seen as logical. People see the contemporary ecosystem as an integrated whole so they don’t see some species as belonging while others do not.’

Much has changed in the Outback since Rose conducted his interviews almost 30 years ago. Camels have exploded in numbers, alarming people by despoiling sacred waterholes and drinking them dry. Thirsty camels have entered desert townships in their desperation for water, damaging houses, toilets, taps, air conditioners, solar panels, pipes, troughs and tanks. In 2019, the hottest year yet in the centre, two springs west of Alice Springs, Ilpilli and Kumulpa, had desperate camels dying on top of each other and Anangu Luritjiku Rangers had the ‘horrible job’ of removing rotting carcasses from the spring areas with a bobcat, then burning them on pyres. In the Tanami Desert the Central Land Council, working with shooters from the Northern Territory Parks and Wildlife Commission, organised an emergency cull of feral cattle, horses, camels and donkeys near Lajamanu to defend springs there. The following year, for the first time ever, a cull of more than 5,000 camels was organised on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands of South Australia, to stop thirsty camels damaging infrastructure and polluting waterholes.

Anthropologist Petronella Vaarzon-Morel and biologist Glenn Edwards have written about Dreaming Law or Jukurrpa which states that animals can be killed for eating but not for nothing, but that said, plans to sell camel meat have come to little, because wild camels are remote from abattoirs and ports. ‘This situation is forcing people to articulate their fundamental values in relation to indigenous and introduced animals’, they wrote. ‘Increasingly, many are concluding that camels do not belong.’

Beliefs within any group vary, and the situation in Central Australia today is that some communities want camels culled and others are holding back. Rose learned that some people were unhappy about camels in the 1990s, and the invasion curve – by which opinions about introduced species can change dramatically as numbers rise and damage increases – means those concerns are much greater today. (The same shift is evident in coastal NSW towns in which newly arriving deer are appreciated until numbers rise and problems emerge.)

Buffel grass and its destructive fires have also increased in Central Australia, and Indigenous communities are siding with environmentalists who want it stopped rather than with pastoralists who want more plantings for cattle.

The Australian 2021 State of the Environment shows that Indigenous communities have deep concerns about invasive species based on ever-increasing damage to Country. Academics who have been arguing otherwise should revisit the evidence.

More information:

References

- Franklin A, (2006) Animal Nation: The True Story of Animals and Australia. Sydney: UNSW Press

- Janke T, Cumpston Z, Hill R, Woodward E, Harkness P, von Gavel S & Morrison J (2021). Australia state of the environment 2021: Indigenous, independent report to the Australian Government Minister for the Environment, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, DOI: 10.26194/3JDV-NH67.

- Rose B, (1995): Land Management Issues: Attitudes and Perceptions Amongst Aboriginal people of Central Australia. Central Land Council Cross Cultural Land Management Project.

- Trigger D (2008) Indigeneity, ferality, and what ‘belongs’ in the Australian bush: Aboriginal responses to ‘introduced’ animals and plants in a settler-descendant society. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14 (3): 628–646.

- Vaarzon-Morel P, and Edwards G (2012) Incorporating Aboriginal people’s perceptions of introduced animals in resource management: insights from the feral camel project. Ecological Management & Restoration 13(1): 65–71