Australia’s Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek has pledged to stop new extinctions. But which species are most at risk of going extinct and what will it take to keep them safe?

Native wildlife on the brink of extinction

The stocky galaxias, a small, mottled fish with a beautiful golden iris, survives in a tiny 3-kilometre stretch of Tantangara Creek above a waterfall in Kosciuszko National Park. The rest of the catchment is now uninhabitable to them because of predatory invasive trout.

This critically endangered fish is unlikely to survive in the wild. According to expert analysis, the stocky galaxias has a 67% risk of extinction within the next 20 years. All it would take would be an angler shifting trout above the waterfall or an extreme storm drowning out that last barrier between the stocky galaxias and invasive trout. If the Snowy 2.0 scheme goes ahead, the stocky galaxias could be wiped out instead by the climbing galaxias. And feral horses are adding to its woes by degrading what little area the stocky galaxias does still inhabit.

Another of our natives unlikely to survive much longer is the critically endangered native guava (Rhodomyrtus psidioides). This shrub or small tree was common on the edges of rainforests in Queensland and News South Wales and important in forest regeneration. But the arrival of a new fungus in Australia has decimated it.

Just 12 years since myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii) was first detected, native guava has been assessed as having a ‘high’ risk of extinction within one generation (about 20 years). Adding to the damage, in some areas native guavas are being replaced by the notorious weed lantana (Lantana camara), making our rainforests more susceptible to fire.

The stocky galaxias and native guava are just two of about 100 unique Australian species that were recently assessed by the now defunded Threatened Species Recovery Hub as having a high or greater than 50% risk of extinction within 10–20 years. Invasive species represent a significant threat to nearly three-quarters of them.

Animals at risk

About 32–42 vertebrate animal species are on this high extinction risk list. The lower number takes into account 10 species that are probably already extinct, although not yet confirmed or recognised formally as such.

Those at highest risk are:

- 22 freshwater fish species

- 8 frog species (4 probably extinct)

- 6 reptile species (4 probably extinct)

- 4 bird species (3 probably extinct) and an additional 8 subspecies

- 2 mammals (1 probably extinct).

Another 20 animals face at least a 30% risk of extinction. Although many more mammals are highly threatened, most are now safer from extinction because they have been translocated to islands and fenced reserves that are protected from predatory foxes and cats.

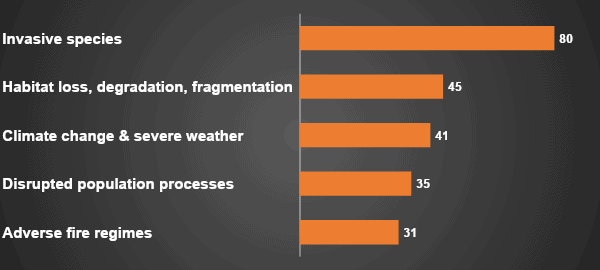

Continuing the pattern of the past 2 centuries, invasive species are the most prevalent threat to at-risk animals. Of the 37 species at high risk for which threats have been rated, 36 are threatened to a high or medium degree by invasive species.

Invasive predators and pathogens dominate, with the most prevalent threats being chytrid fungus (the main threat to native frogs) and invasive trout (a major threat to native freshwater fishes). The list also includes several invasive ungulates (pig, deer, horse). In addition to invasive species, many at-risk species are threatened by habitat loss, adverse fire regimes and climate change.

Plants at risk

Also at high risk of extinction – within 10 years – are 49 plant species. These plants are all only known to exist in a single population or number fewer than 250 individuals while still being in decline. An additional 187 plants were assessed as being at risk of extinction within the next 10–100 years.

Another assessment, published in 2021, predicted the likely extinction of an additional 16 native tree species due to disease caused by myrtle rust. Although this fungus has only been in Australia for a little over a decade, it already infects over 350 native plant species.

Overall, invasive species – mainly myrtle rust, Phytophthora cinnamomi (a water mold), feral herbivores (rabbits, goats, deer, horses) and weeds – are significant drivers of at least 54% of the imminent extinctions predicted for Australia’s native plants.

What will it take?

To meet its pledge for zero new extinctions, the Australian Government will need to greatly boost conservation efforts. Most of the at-risk species have no recovery plan and most of their threats are escalating.

But protecting our natural world is about more than simply preventing all-out extinctions through measures like captive breeding and seed banking. It requires a national focus on abating the major threats that are behind Australia’s extinction crisis. Invasive species, a major driver of so many imminent extinctions, must be a high priority.

To achieve zero new extinctions, we urgently need much more ambition, a more systematic approach, more funding and national coordination to abate the threats that are leaving so many of our native plants and animals teetering on the brink of extinction. This is the focus of the Invasive Species Council’s Threats to Nature project.

More information:

References

- Garnett ST, Hayward-Brown BK, Kopf RK, Woinarski JC, Cameron KA, Chapple DG, et al. Australia’s most imperilled vertebrates. Biological Conservation. 2022; 109561.

- Lintermans M, Geyle HM, Beatty S, Brown C, Ebner BC, Freeman R, et al. Big trouble for little fish: identifying Australian freshwater fishes in imminent risk of extinction. Pacific Conservation Biology. 2020; 26(4): 365-377

- Gillespie GR, Roberts JD, Hunter D, Hoskin CJ, Alford RA, Heard GW, et al. Status and priority conservation actions for Australian frog species. Biological Conservation. 2020;247: 108543.

- Geyle HM, Hoskin CJ, Bower DS, Catullo R, Clulow S, Driessen M, et al. Red hot frogs: identifying the Australian frogs most at risk of extinction. Pacific Conservation Biology. 2022;28: 211–223

- Geyle HM, Tingley R, Amey AP, Cogger H, Couper PJ, Cowan M, et al. Reptiles on the brink: identifying the Australian terrestrial snake and lizard species most at risk of extinction. Pacific Conservation Biology. 2020; 27: 3-12.

- Geyle HM, Woinarski JC, Baker GB, Dickman CR, Dutson G, Fisher DO, et al. Quantifying extinction risk and forecasting the number of impending Australian bird and mammal extinctions. Pacific Conservation Biology. 2018;24: 157–167.

- Silcock J, Fensham R. Using evidence of decline and extinction risk to identify priority regions, habitats and threats for plant conservation in Australia. Australian Journal of Botany. 2018;66: 541–555.

- Fensham RJ, Carnegie AJ, Laffineur B, Makinson RO, Pegg GS, Wills J. Imminent extinction of Australian Myrtaceae by fungal disease. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2020;35: 554–557.

- Garnett S, Baker GB. The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020. CSIRO Publishing; 2020.

- Woinarski J, Burbidge A, Harrison P. The Action Plan for Australian mammals 2012. CSIRO publishing; 2014.

- Chapple D, Tingley R, Mitchell N, Cox N, Bowles P, Macdonald S, et al. The action plan for Australian lizards and snakes 2017. CSIRO Publishing; 2019.