A damning report released by the Victorian Parliament reveals the state’s ecosystems will head into terminal decline without clear and decisive action to prevent the extinction of hundreds of critically endangered animals, plants and ecological communities.

In devoting a whole chapter to the issue, it finds invasive species – weeds, feral animals and invasive pathogens like chytrid fungus – are now a key driver of ecosystem decline in Victoria, outcompeting native animals and preying on wildlife.

The Inquiry into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria finds invasive species are now present in all terrestrial and aquatic environments across Victoria and are damaging the environment, impacting agricultural businesses, creating public health and safety risks and reducing liveability of communities.

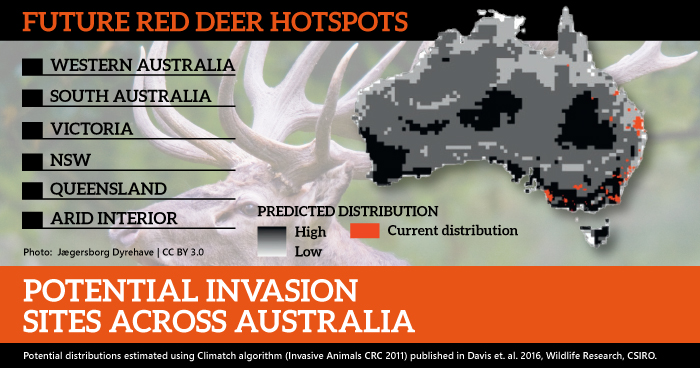

While many invasive species are already widespread in Victoria, including foxes, rabbits and feral cats, the report warns populations of feral deer and pigs are now also expanding rapidly. It finds current state legislation is not keeping up with effective control of weeds and pests.

Much of our work was used in the report, which puts the onus on the Victorian Government to come up with the administrative arrangements and funds needed to enable decisive action that will save hundreds of threatened native species from extinction.

A fox on the hunt in Edithvale wetlands, Victoria. Photo: Wayne Butterworth | Flickr | CC BY-NC 2.0

Invasive species, a key extinction driver

Most extinctions in Australia of our mammals, frogs and birds have been caused by invasive species. Of the roughly 30 mammal extinctions in Australia, about three‑quarters were caused by invasive species. Mostly cats and foxes, but there are other causes as well, for example, black rats.

Climate change, drought, floods and bushfires can all exacerbate and accelerate the spread of invasive species.

In evidence given to the committee that prepared the report our CEO, Andrew Cox, said a clear example of how climate change is amplifying the impacts of invasive species impacts was the loss of snow in the Victorian Alps.

“A good example is the mountain pygmy possum,” he said. “As the snow melts earlier, there is less protection from predators like foxes, so it succumbs. Weeds are more favourable and spread more easily in warmer climates.

“So the two major threats are intertwined, and the impacts of climate change in many cases, or a large number of cases, will be manifest through invasive species causing declines of the native species when they are under climate change stress.”

Oh deer

The report took a close look at feral deer in Victoria, finding clear and consistent evidence the animals are a widespread invasive species, profoundly damaging ecosystems and yet managed under complex and seemingly contradictory status under Victorian legislation.

The Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee recommended consideration should be given to removing deer as a protected species under the Wildlife Act and that legislation should facilitate the effective and humane control of deer across all tenures.

The recommendation comes on top of a 2021 Senate report into the impacts of feral deer, pigs and goats in Australia that came to the same conclusion, recommending all Australian jurisdictions make any necessary changes needed to existing legislative and regulatory frameworks to ensure feral deer are treated as an environmental pest.

The Victorian Government now needs to take this sound, evidence-based advice from these two inquiries and remove the protection of feral deer from the state’s Wildlife Act 1975. This will enable feral deer to be classified as a pest species under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 and effective control of the feral animals to be undertaken.

Alligator weed is a prohibited weed in Victoria and regarded as one of the worst. It invades both land and waterways. Photo: Robert H Mohlenbrock @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA SCS

Control, what control?

In Victoria the Catchment and Land Protection Act is the primary legislation for regulating invasive species, providing a system of controls on weeds and pest animals that regulates their importation, trade, movement, keeping and release.

Under the Act plants may be declared a state prohibited weed, a regionally prohibited or controlled weed, or a restricted weed. Animals can be declared as either a prohibited pest animal, a controlled pest animal, a regulated pest animal, or an established pest animal.

Once declared an established pest species, land owners have legal obligations to prevent the spread of, and as far as possible eradicate, those pest animals occurring on their land. They must also eradicate regionally prohibited weeds and prevent the growth and spread of regionally controlled weeds.

However, evidence presented to the inquiry showed the Act is being under-utilised and poorly enforced. In Victoria 129 pest plants are listed under the Act, about 10 per cent of all environmental weeds present in Victoria. That means 90 per cent of environmental weeds found in Victoria can be bought and sold from nurseries and moved throughout the state without any form of control.

A membership survey conducted by the Ecological Consultants Association of Victoria found that the Victorian Government’s approach to managing noxious weeds under the catchment and land protection Act was considered “very poor”.

“The legislative mechanism exists to enforce the management on invasive weeds on private land, however, it was considered ‘the use of this mechanism is poorly funded, sporadic, and rarely strategic with regards to reducing the worst impacts of weed invasion’,” the association said.

Enforcement of the Act currently sits with Agriculture Victoria, which we have pointed out is clearly focused on controlling the impact of pest species on agriculture.

While many invasive species threats overlap between agriculture and the environment, there are also many that only impact the environment or directly conflict with agricultural interests. As a result, these environmental threats do not receive the attention they deserve.

The objectives and methods needed to manage Victoria’s three million hectares of public conservation reserves differs from those needed to manage agricultural land – Agriculture Victoria’s primary area of expertise.

In our submission to the inquiry we have called for invasive species administration in Victoria to be taken over by the Department of Environment, Land Water and Planning (DELWP), reporting to the state’s environment minister.

Alternatively, we propose that a specialised environmental government agency guided by ecological sustainable development principles with a biosecurity focus could be established.

The need to shift responsibility for invasive species away from Agriculture Victoria to an agency more focused on the environment is clear:

- More invasive species threaten environmental values than agricultural assets and the impact of pest plant and animal species on the natural environment is more difficult to manage.

- Much of Victoria’s ecosystems are managed by the state, whereas agricultural lands are managed by private land owners and industry. Moreover, there are commercial incentives for agricultural management of invasive species, whereas the management of invasive species in conservation reserves relies on government investment.

- Agriculture Victoria has a conflict of interest in relation to invasive species. For example, Agriculture Victoria promotes tall wheat grass for saline areas, a species listed as a potentially threatening process under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act.

To permit or not to permit

The Inquiry into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria found that lists of noxious weed and pest animal species declared under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 are not comprehensive and exclude invasive plants and animals with the potential to devastate Victoria’s biodiversity values.

In its submission to the inquiry, the Victorian National Parks Association pointed out the flaws with a reactive approach to weeds. It stated that there are no restrictions on the trade and cultivation of noxious weeds until they become a problem, “at which point eradication may be impossible”.

The association supported a move to a permitted safe list approach to require a risk assessment to be conducted prior to a new plant species being introduced into the state.

The way forward

The inquiry recommended the Victorian Government develop a legislative reform package to improve the management of invasive species in Victoria.

This would include consideration of a permitted safe list approach, prioritisation of prevention and early action for the control of invasive species, making the Minister for the Environment and their department responsible for administration, and expanding the scope of invasive species legislation to include invasive fish and invertebrates.

The Inquiry into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria was a far-reaching and comprehensive review of the state of Victoria’s natural environment. It was direct and uncensored, unlike many government-led reviews.

If Victoria is to avert the rapidly deteriorating state of its native plants and animals and the systems they depend on, the Victorian Government must urgently implement the results of this inquiry.