TASK 1:

Strengthen Australia’s threat abatement system

The EPBC Act is limited in its ability to manage key threats or quickly respond to acute threats such as bushfires, biosecurity incursions or other natural disasters.

Changes are needed to support more effective planning that accounts for cumulative impacts and past and future key threats and build environmental resilience in a changing climate.

10-year review of the EPBC Act (2020)

1

Comprehensively identify and list threats to nature through an independent scientific process and regularly review the list to ensure it remains up to date

Australia needs a comprehensive, authoritative list of key threats to nature. Decisions about which threats meet the criteria under the EPBC Act are scientific in nature and should be made by scientific experts. Removing ministerial discretion will make the listing process more credible, consistent and efficient. The appropriate body for determining listings is the Threatened Species Scientific Committee or an equivalent expert body. The option for public nomination of threats should be retained to ensure that emerging or poorly known threats are also assessed

2

List threats in a hierarchical scheme of key threatening processes and threats of national environmental significance

3

Establish an additional threat category – emerging threatening processes

4

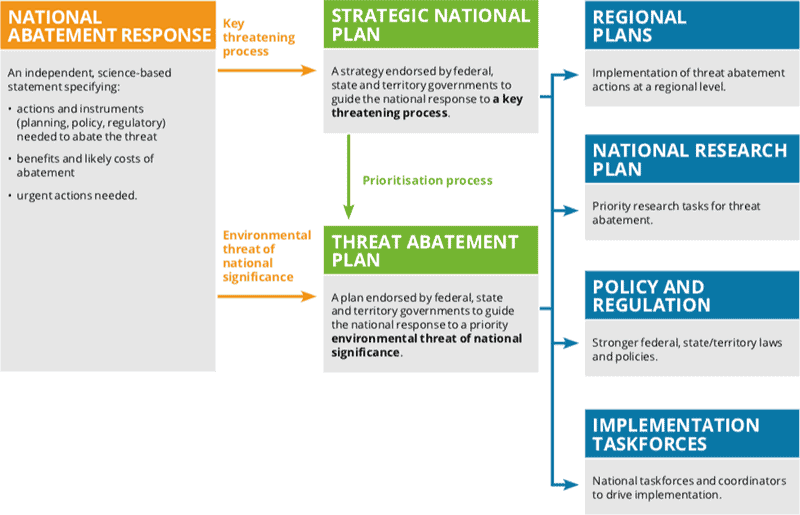

Design a fit-for-purpose national abatement response for all listed threats, including national and regional plans, and policy and regulatory responses

If a threat is serious enough to be listed under the EPBC Act, it warrants a national abatement response. The response options should be flexible, encompassing planning and policy, to enable abatement of different types of threats.

Stage 1: For all key threatening processes (high level threats) and environmental threats of national significance (specific threats), develop a threat response statement. This should be an independent, science-based statement of what actions (management, research) and instruments (plans, policies, regulations) are needed to abate the threat, specifying the urgency, benefits and likely costs of abatement.

Stage 2: For key threatening processes, develop strategic national plans specifying the intended abatement responses by federal, state and territory governments. Certain aspects of key threatening processes may warrant standalone national plans, such as a national restoration plan (in response to habitat destruction) and a plan for protecting climate refugia (in response to climate change). For priority environmental threats of national significance, develop threat abatement plans or action plans, unless abatement can best be achieved in other ways such as regulatory or policy changes. Planning should be flexible, able to address partial aspects of a threat and encompass actions to address non-environmental impacts.

Stage 3: Implement strategic national plans and threat abatement plans, including by:

- strengthening relevant laws and policies (federal, state or territory)

- undertaking research, as specified in abatement or action plans and as prioritised in a national research plan

- managing threats, including through regional plans.

5

List key threatening processes as matters of national environmental significance

This will facilitate federal regulation of activities that significantly exacerbate threats to nature and intervention when threats are intensifying and need urgent action. Achieving abatement will require the federal government to exercise its constitutional powers when there are regulatory failures by some states and territories, as exemplified by land clearing and the high-risk use of invasive species.

6

Establish an implementation taskforce for each threat response

A taskforce with expertise and stakeholder representation (government and non-government) is essential to drive implementation of threat abatement plans. This has been a consistent feature of effective plans.

7

Systematically monitor and report on threat abatement progress

A national biodiversity monitoring and reporting framework (underpinned by standards) should include a focus on the status of each major threat, whether or not it is subject to a threat abatement plan, and the status of biodiversity impacted by each threat. Reporting requirements should be harmonised across projects and programs to enable tracking of national progress.