Invasive Species Council CEO Andrew Cox reflects on a recent visit to the red fire ant eradiation program HQ and the first ever outbreak of the highly invasive ants on Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island).

“How did these killer tiny ants cross the water?” That was my first thought when I received the call that red fire ants had made it to Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island), off the coast near Brisbane Queensland.

If you are not familiar with it, Minjerribah is a place of incredible cultural significance, a sanctuary that has been cared for by its owners and custodians, the Quandamooka People, for thousands of years. These high cultural values, along with its impressive conservation values – two nationally threatened peatland fish, six threatened plant species, its perched and water table window freshwater lakes and littoral rainforest – meant that the Quandamooka’s pursuit of World Heritage listing was entirely warranted. Minjerribah’s wetlands, foreshore swamps and interconnecting land are also listed as part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site.

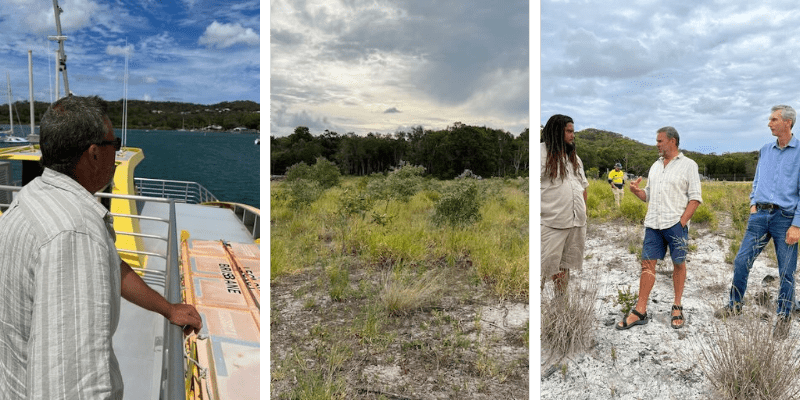

So you can appreciate my concern during this call. I knew that the Red Fire Ant Program was at risk due to a lack of funding. To find out exactly what was going on I headed to Queensland, with Richard Swain, our Indigenous ambassador.

This isn’t the first time I’ve had a call like this. Red fire ants were first detected in Brisbane’s suburbs and the Port of Brisbane in 2021, and subsequent outbreaks occurred in Gladstone, Port Botany and Perth. Since then the ants have been eradicated or are well on the path to eradication in all places except one. Brisbane was the largest outbreak and has been the hardest. A National Red Fire Ant Eradication program has been in place for well over 20 years to stop these tiny killers from taking over their backyards, farms, parks and environment.

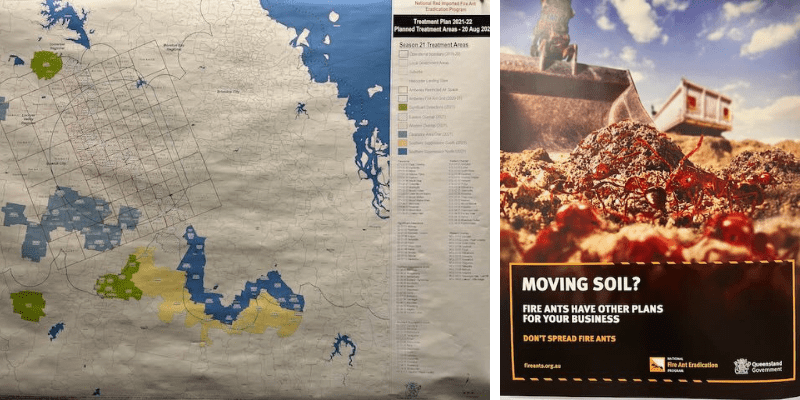

Thankfully, despite many setbacks these efforts are largely working, and the treatment regime and biosecurity measures in place have slowed the spread and started to remove ants from many areas. It’s an incredibly complex undertaking across hundreds of suburbs over an area of 6,000 km2 , or roughly twice the size of the ACT. In 2017, thanks to a concerted two-year campaign run by the Invasive Species Council, federal, state and territory governments made a ten-year, $411M commitment to eradicate the red fire ants when the program was close to being abandoned.

It’s well worth the effort and money. CSIRO’s ant expert Dr Ben Hoffman says red fire ants are ‘one of the world’s worst invasive species. For a very good reason’. They swarm in their thousands and kill people, small pets and livestock. They can wipe out entire native ecosystems and turn bustling grasslands and forests silent. They do this by rapidly overwhelming an animal (or human) when disturbed, and stinging in unison. Their coordinated attack overwhelms the nervous system of the victim and can cause anaphylactic shock.

Six years after the injection of new funds, what’s troubling is the results of an independent review of the program. It found that while eradication is still technically feasible, success success may only be possible with changes to the program and a major boost to funding.

The Brisbane outbreak has proved difficult as it’s a highly populated area and with three years of rains and flooding it’s been hard to stop the fire ants spread. These tiny killer ants are smart, highly organised and work in social super colonies. They hitch rides in pot plants, on trucks carrying soil and building waste, and even in cars. To ensure we stop the spread and completely eradicate them, we need to give this all we’ve got, as soon as we can.

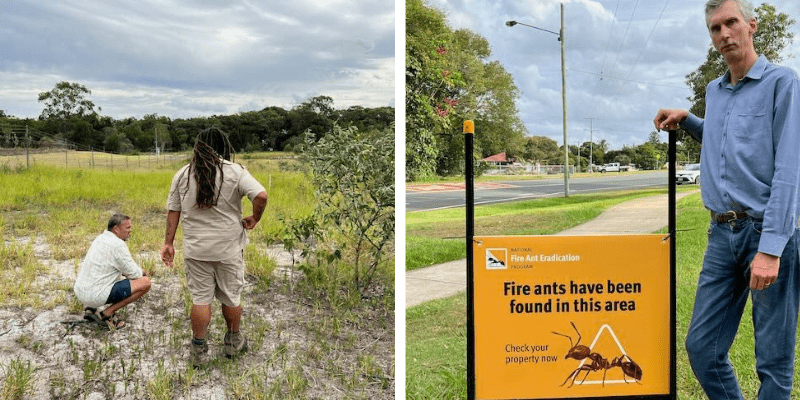

Currently, the ants are on the move making their way westward, ever closer toward the Murray Darling Basin watershed, while to the south they’re in parts of the Gold Coast, as close as 12 km from the NSW border. And thanks to human assisted movement, they have just crossed the ocean passage to Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island).

When we arrived at Minjerribah, we were met by the staff of the Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation. They were an impressive, highly organised group. They shared their hard won success protecting the island’s shorebirds from foxes, having eliminated foxes from most of the island except near the townships where baiting is not possible. They had been turning their efforts to the small population of feral cats, when they got the news in late January: red fire ant nests had been found on the island in a former sand mining site undergoing rehabilitation.

While we still don’t know how they got there, genomic testing done at the time has shown the colonies are unrelated, meaning they are unlikely to have arrived by themselves and most likely spread from the import of contaminated material. We left Minjerribah with a heavy heart, but high hope, confident that the Quandamooka people will handle this in the same competent way they have dealt with the feral animals, working under the auspices of the eradication program and properly funded to play their role.

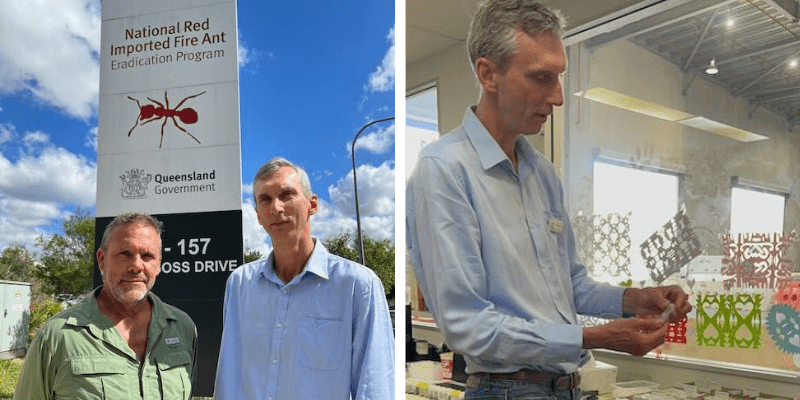

The next day, we met the head of the eradication program, Lance Perry, and operations manager, Graeme Dudgeon at the Berrinba headquarters of the red fire ant program that also served as one of the depots for their ground eradication teams. The scale of the operation was apparent. We toured the building and spoke to many of the staff.

I’ve got to hand it to them, they are doing such a difficult job across such a vast area. What was obvious was the deep care these red fire ant experts had for protecting the Brisbane community and nature from these ants.

I recalled the warnings from those I met on my red fire ant tour to the United States in 2016, a place where fire ants are out of control across the entire southern US. They told me, “If we could go back in time, we’d do it differently. We’d give it everything we’ve got”.

I felt the weight of the world. “I’d give up one of our nuclear submarines and spend that cash to defend our country from the current occupation of red fire ants,” I thought. Despite the uncertainty about whether the program will receive the funding it really needs, the program’s team face every day with confidence and intelligence. These people were taking this in their daily stride, preventing a living nightmare from spreading across the country.

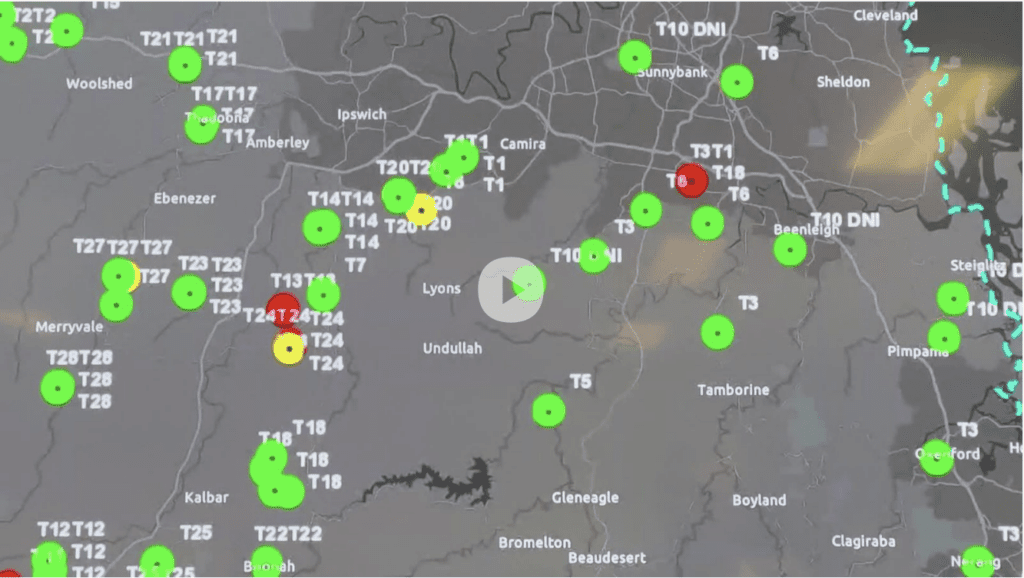

So, how does a critical operation like this work? There are two major operations in place. The western portion of the infestation centred on the Lockyer Valley undergoes broadscale treatment. The aim is to lay low-toxicity bait across all the entire treatment areas, regardless of whether nests are visible. Baits can be dropped from the air in remote locations, and by ground teams near homes and built-up areas. The area usually needs to be treated 3 times over two years for successful eradication, after which intensive surveillance identifies areas of remaining ants for spot treatment.

For the areas outside the intensive treatment areas, rapid response teams respond to public calls to treat areas which pose a high risk to people. Each nest identified is treated with an insecticide and the surrounding areas several metres either side receives a prophylactic low-toxicity bait. Turnaround time is much improved from several years ago, now averaging 1-3 days from receiving a report. These areas will ultimately receive the thorough treatment once the westerly portion of the infestation area is successfully dealt with.

Not everything always goes to plan. The weather needs to be just right for the intensive treatment. Too hot is not good, too much rain doesn’t work either.

Andrew attacked by an uncontrolled red fire ant! An active public awareness campaign uses targeted advertising and warnings. They even have a red fire ant suit to capture the attention of the young at heart adding an element of fun knowing that, when battling these heavy issues, a little light humour helps ease the pressure.

The community in the vast fire ant zone in Brisbane’s southern suburbs and areas to the south and west are our real heroes of this program. For more than 20 years many of them have had to put up with movement restriction and property treatments and keep a lookout for the ants. We rely on their support and cooperation for eradication success. From me and the team, I want to give a grateful shout out for their efforts.

The team at the National Red Fire Ant Eradication Program, the Brisbane Community and the Quandamooka people of Minjerribah are doing an outstanding job protecting us from a life long sentence of living with red fire ants.

So after seeing all of this, it was clear that the Invasive Species Council has a big job ahead. We need to urgently secure the funds from the federal, state and territory governments for the expanded eradication program that the expert review called for. To help us achieve this, we have just recruited Brisbane-based Reece Pianta to head up a new fire ant campaign over the coming months. Reece led our successful campaign in 2016 and 2017 that resulted in the ten-year eradication funding.

We are working hard to get federal, state and territory governments to allocate the needed funding for eradication. Now is our chance to prevent this. Not next year or next decade. Together, we need to demonstrate that Australians want governments to allocate the required funding now and stop these deadly infestations before it’s too late.

To support our campaign, you can make a donation to our red fire ant appeal.