Jack Gough leads the campaign to protect the Australian Alps at the Invasive Species Council. He recently visited Kosciuszko National Park with Penny Sharpe, NSW’s new environment minister, where they faced the challenge of reducing feral horse numbers after years of delay and inaction.

‘It’s never been this bad. There are horses everywhere,’ exclaimed Richard as we hit the brakes to avoid a mob of 40 odd feral horses on the road and grazing in the snow gum forest.

‘This is meant to be a national park, but they’re turning it into a horse paddock,’ Swain mused.

Richard Swain, snowy river guide and Invasive Species Council Indigenous Ambassador, our conservation director James Trezise and I were heading out to Currango Homestead in the northern part of the park, to meet NSW environment minister Penny Sharpe.

The Labor Party had just formed government following the NSW election, and the new Minister was touring the park with national parks staff to understand the scale of the feral horse problem. We were invited to brief her on the science and the tough choices she will need to make to save our native animals and protect our alpine streams.

In opposition, she and many other Labor MPs had been advocates for greater action on feral horses, criticising the delay and inaction that’s led to a population boom.

The threat of feral horses to our national parks and native wildlife was a hot election issue, with regular, high-profile media coverage, due in large part to the work of the Invasive Species Council and thousands of engaged supporters. Ahead of the election, Labor had promised to ensure there were extra resources to meet the current management plan’s target: reducing the feral horse population to 3,000 by 2027 (from about 18,500 currently). NSW Labor also promised to fund 100 extra dedicated NPWS pest and weed field officers.

Face-to-face with feral horse damage

This trip was a deliberate demonstration of her concern about threatened species like the corroboree frog and broad-toothed rat and her commitment to take action.

When we greeted minister Sharpe, she had just flown over the park in a helicopter to survey the damage caused by feral horses. She was also accompanied by independent member for Wagga Wagga, Dr Joe McGirr.

Dr McGirr’s electorate takes in the western part of Kosciuszko National Park. He had been very outspoken during the election campaign about the issue. He even made it clear that action on feral horses would be a condition of his support in the event of a hung parliament.

Our meeting was important because, following the NSW election, the campaign to save the Snowies from feral horses is at a critical juncture.

We have had significant success in recent years in shifting policy, the politics and the public debate. The main driver for protecting the feral horse, former Deputy Premier John Barilaro, has left the parliament. We now have a NSW Environment Minister who has an electoral mandate for action, has made reducing feral horse numbers a priority and has committed to greater resources.

However, the real test will be whether meaningful and rapid reductions are actually achieved on the ground. Years of delay and inaction mean business-as-usual is not an option.

Later that day, we sat around the old dining table at Currango Homestead, and laid out for the Minister the stark reality: the current management plan is off track. Getting it back on track will be a big task.

Getting alpine protection back on track

Our NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service staff have been doing an incredible job under difficult circumstances to safely, professionally and humanely remove feral horses from Kosciuszko National Park. Unfortunately, their dedicated efforts have been undermined by underfunding, political interference and arbitrary restrictions on effective control methods. They have also faced appalling threats of violence, intimidation, abuse and disruption of their work from pro-feral horse activists.

Despite record numbers of horses removed in 2022 (859), removals are well below what’s required to actually reduce the population. Instead of a reduction, we have seen a 30% increase in numbers in the past two years. Each year control is delayed or deferred will increase the number of feral horses required to be removed and the cost of an effective control program.

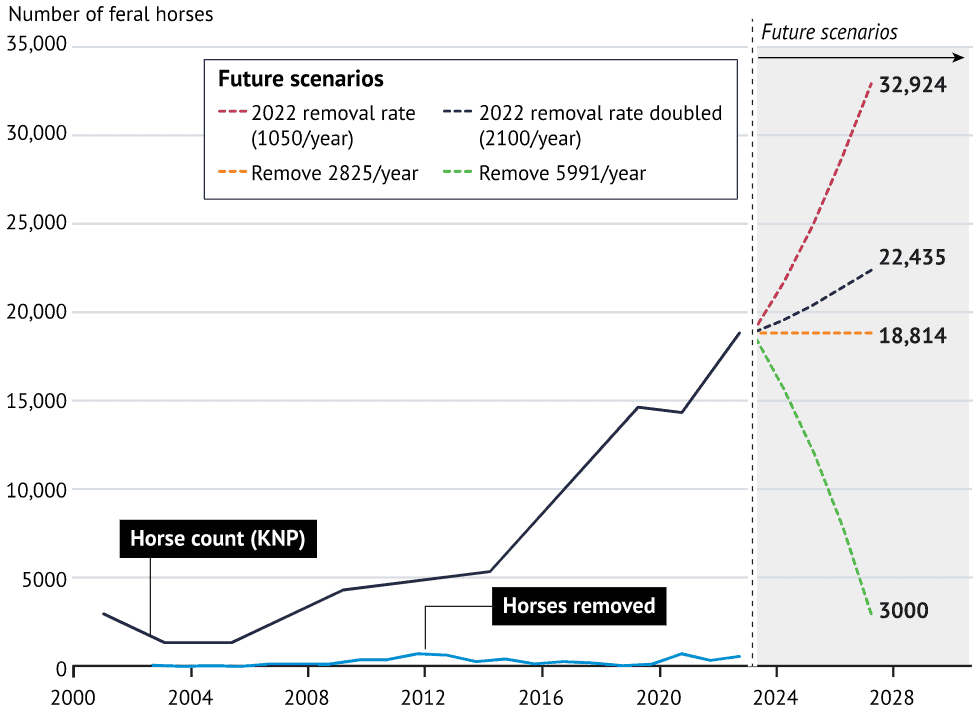

In our briefing we showed the Minister modelling that has been conducted of future population scenarios, depending on the rate of removal. This modelling finds that:

- At the current rate of removal, the population could reach ~33,000 by 2027,

- To stop the population from growing, about 2800 feral horses must be removed annually, and

- 6000 feral horses need to be removed annually to reach the target of 3000 by 2027.

As we drove home across the Currango Plain to Long Plain and back to Cooma, there were horses almost everywhere we looked – groups of between 2 and 10 dotted across the landscape in every direction as far as the eye could see.

At one point we stopped to walk from the road down to a small mountain stream where a group of 8 horses were grazing and churning up the banks. In that short 30-metre stretch, I counted the piles of horse dung to one metre either side of me. I counted 15 piles.

Seventy years after we removed cattle from the High Country and decided as a nation to protect this incredible area and its unique wildlife, it’s clear Kosciuszko National Park is being turned back into a paddock.The good news is we have time to remove the horses and save the Snowies. But getting there will take dedicated and delicate advocacy, political courage and a willingness to heed the advice of our incredible national parks staff.

Thank you!

We asked our NSW supporters to step up and take action during the recent election and you delivered in spades. Together we won many commitments including urgently reducing feral horse numbers and 100 new national parks staff focussed on pests and weeds.

Our results for Kosciuszko National Park and nature across NSW are just the beginning and clear evidence of what we can achieve together when we take action. We should have enormous hope for the future of wildlife and biodiversity across Australia.