Stopping the fox eradication program in Tasmania may go down in conservation history as one of the most short-sighted decisions ever made, risking the future of the island’s native mammals and wasting the investment to date.

On 4 June the Tasmanian Minister for Environment, Parks and Heritage, Brian Wightman announced there will be no more funding for fox baiting, and the program will move to active monitoring. Twenty-four contractors will lose their jobs on 30 June. He declared the fox eradication a success on the basis that no evidence of foxes has been found in the last 18 months. But the report summarising the current evidence on which he based his decision has not been released and pest experts warn it is too early to claim success.

The fox was first found in the state more than 10 years ago after what is believed to be the deliberate release of numerous foxes in up to three locations (1999) and the sighting of a fox leaving a ship at Burnie docks (1998).

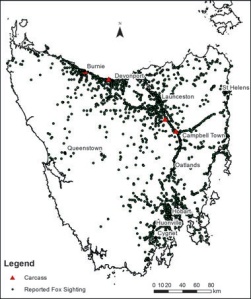

A recent paper by Sarre et. al. (2012) summarises the extent of evidence of foxes in Tasmania: over 2,000 unconfirmed sightings, four fox carcasses (male, female and immature), 56 confirmed scats and 47 ‘fox-like’ scats.

The paper concludes: ‘Our data suggest that foxes could be on the verge of becoming established irreversibly in Tasmania. Given their apparent widespread distribution, the moment may even already have passed for a feasible eradication although we do not suggest that now is the time to stop…we suggest that a massive upscaling of effort and perhaps more focused approach is going to be required to maximize the chances of a successful eradication. Otherwise, Australia stands on the precipice of a third major wave of mammalian extinctions – this time focused on the island of Tasmania.’

In publicising the paper, Professor Sarre said, ‘The present situation could be as serious a threat to the pristine Tasmanian environment as the previous extinction wave was to Australia’s mainland fauna, following the arrival of Europeans and which has so far wiped out more than 20 species.’

The paper presents a map showing the distribution of fox sightings and carcasses.

Local criticism of the $50 million program had been strong and growing, with some believing that there were never any foxes in Tasmania and that the evidence for foxes resulted from a grand conspiracy or a costly hoax.

Such claims are part of a broader trend of distrust in government and dismissal of science. For a government to make decisions on the basis of such criticisms and contrary to scientific advice is to embark on a dangerous path.

Even on Macquarie Island, where they have just rid the island of rabbits and rats, there is a two-year followup program to make sure that no area was missed.

For the much larger area of Tasmania, where it is impossible to bait all areas at once, maintaining the baiting program is essential to reduce the risk that the fox remains.

The fox is an incredibly elusive animal. At low numbers, it is unlikely to be seen by people. However, once it becomes populous enough to be evident, it would be extremely hard to eliminate. When there is already compelling evidence of the fox in Tasmania, it doesn’t make sense to stop the eradication program and wait to see if evidence (a live fox or fresh carcass) eventuates to silence the critics.

The Invasive Species Council has taken the advice of invasive animal scientists and does not believe that enough time has passed to stop the baiting program. Given the massive consequences if the fox were to establish in Tasmania, it is far more prudent and cost-effective to continue eradication until it is reliably certain that there are no foxes left.

We urge you to write to Tasmanian Premier, Lara Giddings, encouraging her to restart the precautionary but absolutely necessary eradication program.