MEET THE INVADERS

Cats

Patient, silent killers with remarkable night vision and sharp claws – feral cats are one of the best hunters in the world.

Their agility and powerful jump/launching allow them to stalk and capture prey with precision.

The domestication of cats started probably about 10,000 years ago in the Middle East, when humans became farmers and their grain stores attracted mice.

The main ancestor of the domestic cat is the widespread Afro-Asiatic wildcat (Felis lybica), native across Africa, the Middle East and parts of Asia.

Here their numbers are kept in check by larger carnivores like leopards, lions and hyenas.

For the feral cat, their ability to thrive in harsh environments – from the outback to the rainforest – makes them incredible survivors.

Feral cats are lone night hunters, prowling the dark with stealth and skill! They only eat meat, usually from animals they hunt themselves. They kill a wide variety of prey, from tiny beetles to mammals weighing up to 4 kilos!

Even if well-fed, they can’t ignore their hunter instincts.

They are also prolific breeders. Cats can reproduce from as young as 5 months of age, and every year produce up to 3 litters, each with an average 4–6 kittens.

Invasion story

The domestic cat arrived with the First Fleet in 1788. While there’s been speculation about earlier introductions, historical records and genetic studies strongly indicate that European sailors and settlers were responsible for their initial arrival.

Initially, cats stayed close to human settlements. However, their populations began to spread as settlements and pastoralism expanded across the continent, with cats either escaping or being deliberately released to control rabbits (despite little evidence of effectiveness).

This spread accelerated significantly around 1880 with the limits of pastoral settlement being reached, allowing cats to rapidly colonise desert regions.

In an unprecedented ecological event, cats expanded across approximately 7.6 million square kilometres in just 70 years.

By 1890, historical records show cats had established everywhere on the mainland and Tasmania, except for a small area in the north Kimberley and some offshore islands.

The domestic cat arrived with the First Fleet in 1788. While there’s been speculation about earlier introductions, historical records and genetic studies strongly indicate that European sailors and settlers were responsible for their initial arrival.

Initially, cats stayed close to human settlements. However, their populations began to spread as settlements and pastoralism expanded across the continent, with cats either escaping or being deliberately released to control rabbits (despite little evidence of effectiveness).

This spread accelerated significantly around 1880 with the limits of pastoral settlement being reached, allowing cats to rapidly colonise desert regions.

In an unprecedented ecological event, cats expanded across approximately 7.6 million square kilometres in just 70 years.

By 1890, historical records show cats had established everywhere on the mainland and Tasmania, except for a small area in the north Kimberley and some offshore islands.

How did we get here?

Australia’s battle against feral cats has been a story of underestimation, plagued by inconsistency and underfunding.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that they were widely recognised as a major threat.

Feral cats were listed as a key threatening process under the national environmental law in 2000. But progress on reducing the threat has been slow. Feral cat control has mostly been sporadic, under-resourced and poorly coordinated. More research is needed to develop consistently effective methods.

The most effective programs have been the eradication of feral cats on islands, including world-heritage-listed Macquarie and Dirk Hartog islands, to create cat-free havens for threatened mammals.

For domestic cats, some states, like the ACT lead the way with mandatory cat registration and containment laws, but others like New South Wales have lagged, creating significant gaps.

A series of national threat abatement plans, the first in 1999, have included promising elements, but have been poorly implemented.

In 2015 a national plan was released, which included some promising elements such as an increase in predator-free havens and island eradication programs, however, the fragmented funding was grossly inadequate for meeting the plan’s objectives, leading to limited progress.

In 2020 a parliamentary inquiry into feral and domestic cats recommended a reset of current policy and planning, including a new iteration of the national plan and a revised Threatened Species Strategy.

A new threat abatement plan was released in 2024. Encouragingly, all state and territory governments (except Queensland) have agreed to jointly implement it.

It includes strategies like island eradication and supporting Indigenous rangers but at least $60 million over the next 4 years is needed to see the ambitious plan come to life for our native species.

In 2025, the NSW government announced a review of its Companion Animals Act 1998 which currently prohibits councils from being able to require cat containment. This followed a NSW cat inquiry which the Invasive Species Council strongly campaigned for.

The toll on nature

Feral cats might look like your cuddly companions, but they’re a different beast. Together, feral and pet cats are an environmental disaster in Australia.

Why? Not only are they highly skilled hunters, but since the decline of Tasmanian devil and dingo populations, there isn’t anything to hold them back.

Australian wildlife evolved without cat-like predators and often have low reproductive rates, making them especially vulnerable to such efficient hunters.

Fire, livestock grazing and land clearing make things worse by creating open hunting grounds where cats can easily target ground-dwelling species.

Unfortunately for so many of our native wildlife, they are the perfect-sized snack.

On average, cats kill 2.92 million mammals, 1.67 million reptiles, 1.09 million birds, 0.26 million frogs and 2.97 million invertebrates every 24 hours. It’s a wildlife emergency!

A single feral cat in the bush can kill around 791 native animals annually, with domestic cats killing an average of 186 when allowed to roam.

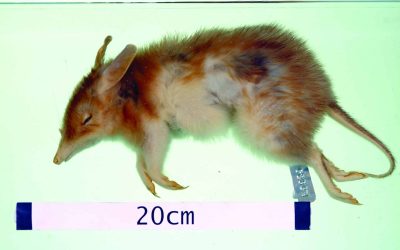

Since colonisation, these natural hunters have driven at least 25 native species, like the desert bandicoot and lesser bilby, to extinction, causing more mammal extinctions than any other invasive species or environmental threat. This is often in combination with foxes.

Sadly, many of our most vulnerable wildlife continue to fall prey to cats, like numbats or the Western ground parrot, of which only 150 remain.

Cats are one of Australia’s most damaging invasive species, they have caused the extinctions of many native species and are still driving population declines today. However, in the past 10 or so years our knowledge of how best to limit cat impacts has improved enormously, and with the right management tools used strategically, there is no reason why another Australian native species need go extinct because of cats.

Professor Sarah Legge

Cultural consequences

But it’s not just hunting that is the problem.

Cats can also spread diseases that can harm native species, livestock, and humans.

For First Nations people, they can threaten native species that hold deep cultural and spiritual significance for communities, fracturing connections to Country.

How do we fix this?

To protect native wildlife and prevent further cat-driven extinctions, we need to see rapid action and greater investment.

Feral cats:

With current technologies, there is no way of eradicating feral cats, except on islands.

Feral cats need to be intensively managed in areas of high conservation significance where critically endangered or endangered species are at risk. For highly susceptible species, creating predator-free havens – by eradicating cats from islands or fenced mainland reserves – is often their best hope of survival.

We need greater investment in feral cat management, research and innovation for more broadscale control methods to give native species cover from predators like feral cats and foxes and increased uptake of new control tools such as Felixer grooming traps. There is also need for more research to better understand the potential for dingoes to suppress cat populations and activity.

Pet cats:

Feral cat management is just one piece of the puzzle. Mandatory microchipping and desexing for all pet cats by 4 months of age, education for pet cat owners and, most importantly, 24-7 cat containment will prevent pet cats from killing wildlife and going feral.

24-7 cat containment isn’t just good for wildlife; it’s better for the cats, too. Cats kept indoors live longer, have fewer vet bills and are safe from the dangers of cars, predators and diseases.

Some local councils, like those in the ACT and some in Victoria, South Australia and Queensland, are leading the charge, with mandatory cat containment. But outdated laws in some states, like New South Wales and Western Australia, prevent councils from implementing these policies.

The Invasive Species Council continues to be a strong voice in the campaign to implement cohesive cat containment laws across the country. We continue to push for the full implementation of the national threat abatement plan and for every state and territory to prioritise the delivery of effective control programs. They should allow the full suite of feral cat control tools to give land managers the best chance of driving down feral cat numbers and protecting our precious wildlife from extinction.

FAQs

Feral cats are unowned cats that live and reproduce in the wild. They have little or no reliance on humans for food or shelter and are often wary of human interaction. Domestic cats, on the other hand, are typically owned pets that rely on humans for their care, including food, shelter, and medical attention. While some domestic cats may roam outdoors, they are generally socialised to humans, whereas feral cats are not. However, both have the same genetic makeup.

Feral cats are found across all states and territories in Australia, but their numbers are highest in areas with abundant prey and suitable shelter, such as arid and remote regions. Estimates suggest that the population of feral cats can surge dramatically during favourable conditions, with numbers exceeding 6 million nationwide. Efforts to quantify exact populations are ongoing, as their distribution and density vary with environmental conditions.

- Baiting: Specialised baits are designed to target feral cats with minimal impact on non-target species.

- Shooting: Ground shooting by trained professionals is used in targeted areas, particularly where baiting or other methods are less effective.

- Trapping: Live trapping is sometimes employed to capture and euthanise feral cats, particularly in areas where their impact is critical.

- Fencing: Predator-proof fences have been built in a few places to exclude feral cats from areas with vulnerable native species.

- Felixers: These advanced devices are a cutting-edge solution in feral cat management. Felixers are automated, sensor-driven units that identify feral cats using facial recognition technology and spray them with a targeted poison gel. This method minimises harm to non-target species and works even in remote or challenging environments.

- Thermal imaging and drones: New technologies, including drones equipped with thermal imaging cameras, are increasingly being used to detect and track feral cats in remote or dense bushland areas, improving monitoring and control efforts.

Invasive Animals Ltd. (n.d.). Feral cats in Australia. PestSmart. Retrieved December 13, 2024, from https://pestsmart.org.au/toolkit-resource/feral-cats-in-australia/

NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub. (2019). The impact of cats in Australia. Project 1.1.2 Research findings factsheet. Available at: https://www.nespthreatenedspecies.edu.au/media/2j1j51na/112-the-impact-of-cats-in-australia-findings-factsheetweb.pdf

Hull, G. (2021). The Ferals that ate Australia. Black Inc

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. (n.d.). Feral cats in Australia. Retrieved December 13, 2024, from https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/invasive-species/feral-animals-australia/feral-cats#:~:text=Feral%20cats%20in%20Australia%20kill,and%2037%20listed%20migratory%20species.

Legge, S., et al. (2020). We need to worry about Bella and Charlie: The impacts of pet cats on Australian wildlife. Wildlife Research, 47, 523–553. Available here: https://www.publish.csiro.au/wr/fulltext/wr19174

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. (n.d.). Tackling feral cats and their impacts: FAQs [Fact sheet]. Retrieved December 13, 2024, from https://www.agriculture.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/factsheet-tackling-feral-cats-and-their-impacts-faqs.pdf

Threat Abatement Plan for Predation by Feral Cats (2023). Australian Government.

Nilson, S.M. et al., Genetics of randomly bred cats support the cradle of cat domestication being in the Near East, Heredity, vol. 129, no. 6, 2022, pp. 346–355, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-022-00568-4.

Laurie, V., Feral cats a problem for rare ground parrot, Australian Geographic, 19 June 2012, https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2012/06/feral-cats-a-problem-for-rare-ground-parrot/.

Bennett, M., ‘Population of critically endangered numbats in WA’s south stronger than expected, study shows,’ ABC News, 4 February 2024, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-02-04/endangered-numbat-numbers-higher-than-thought-southern-wa/103419552.

Woinarski, J.C.Z., Legge, S.M., & Dickman, C.R. (2019). Cats in Australia: Companion and Killer. CSIRO Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1071/9781486308446

Invasive Animals Ltd. (n.d.). Feral cats in Australia. PestSmart. Retrieved December 13, 2024, from https://pestsmart.org.au/toolkit-resource/feral-cats-in-australia/

NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub. (2019). The impact of cats in Australia. Project 1.1.2 Research findings factsheet. Available at: https://www.nespthreatenedspecies.edu.au/media/2j1j51na/112-the-impact-of-cats-in-australia-findings-factsheetweb.pdf

Hull, G. (2021). The Ferals that ate Australia. Black Inc

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. (n.d.). Feral cats in Australia. Retrieved December 13, 2024, from https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/invasive-species/feral-animals-australia/feral-cats#:~:text=Feral%20cats%20in%20Australia%20kill,and%2037%20listed%20migratory%20species.

Legge, S., et al. (2020). We need to worry about Bella and Charlie: The impacts of pet cats on Australian wildlife. Wildlife Research, 47, 523–553. Available here: https://www.publish.csiro.au/wr/fulltext/wr19174

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. (n.d.). Tackling feral cats and their impacts: FAQs [Fact sheet]. Retrieved December 13, 2024, from https://www.agriculture.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/factsheet-tackling-feral-cats-and-their-impacts-faqs.pdf

Threat Abatement Plan for Predation by Feral Cats (2023). Australian Government.

Nilson, S.M. et al., Genetics of randomly bred cats support the cradle of cat domestication being in the Near East, Heredity, vol. 129, no. 6, 2022, pp. 346–355, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-022-00568-4.

Laurie, V., Feral cats a problem for rare ground parrot, Australian Geographic, 19 June 2012, https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2012/06/feral-cats-a-problem-for-rare-ground-parrot/.

Bennett, M., ‘Population of critically endangered numbats in WA’s south stronger than expected, study shows,’ ABC News, 4 February 2024, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-02-04/endangered-numbat-numbers-higher-than-thought-southern-wa/103419552.

Woinarski, J.C.Z., Legge, S.M., & Dickman, C.R. (2019). Cats in Australia: Companion and Killer. CSIRO Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1071/9781486308446